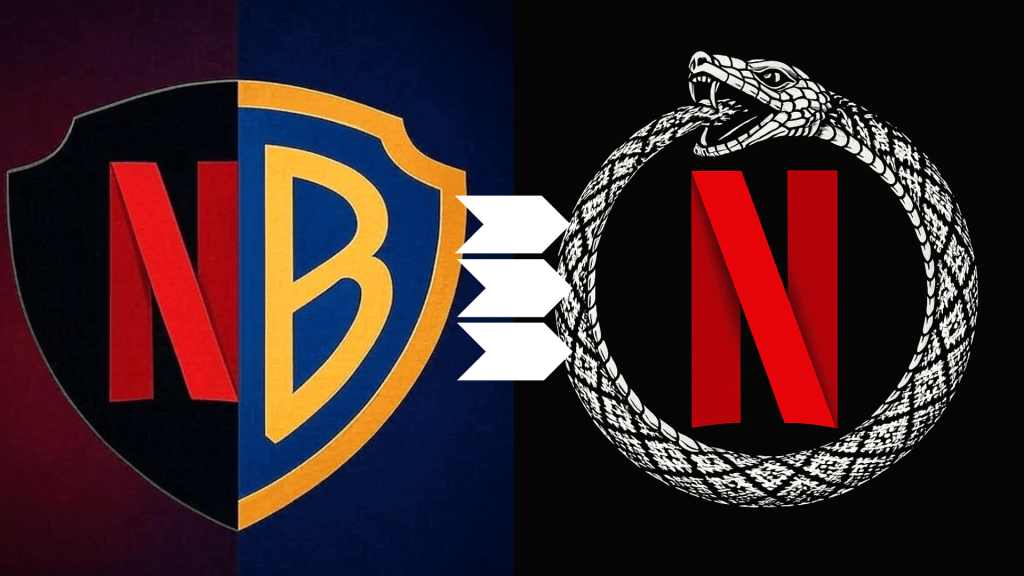

Earlier today, just before the stock market opening, Netflix announced that it would enter into a deal to wholly acquire Warner Bros Discovery, which includes their movie collections, associated IP like the DC Universe, streaming business, and the movie and TV production studios. According to their press release, this deal is hailed as a great step forward in bringing two important entities together which will ensure a glowing future for the go-forward company that will be able to serve their customer base better by providing a wider variety of movies and TV shows, alongside producing and distributing theatrically new and exciting entertainment projects. And while the online commentariat is of two minds about this announcement—predominantly because it is a movie that consolidates the entertainment business around a shrinking number of big Hollywood players—I believe that it also denudes the inescapable truth about the movie streaming business: that it was never going to be profitable or scalable in the first place.

When Netflix came about and disrupted the entertainment industry stack, first with its mail-in DVD service and then with the introduction of a subscription-based platform where customers could access their entire library in exchange for a single flat fee, everyone took notice. Following some initial skepticism, which is to be expected whenever any little tech whippersnapper turns up to upset an ossified business model (think of Uber or AirBnB), other major players figured out that there was money to be made in the streaming market. And this is where the problem really lies because the market has a hard ceiling. It is limited by the number of accessible households. Therefore, the idea that a company in this space could reliably and sustainably scale ad infinitum is for the birds. And it’s not a new concept either. This is evident in the telecommunications market, and used to be true for the business that streaming superseded—cable TV. It’s hard to grow the size of the pie and once market saturation is reached, you can’t reliably sell the same service to the same customer twice.

Granted, Netflix and other streaming players have expended considerable resources to widen their global reach but the return on investment here is difficult to scale as well because the average revenue per user in the US or the UK will be vastly different than in India, Indonesia or Nigeria; three massively populous countries, most of which are yet to be connected to high-speed Internet. The likely reason why this has not been as apparent as it perhaps should have been is because most big players in the streaming market are quite a bit different than Netflix, which is the only one of them for whom streaming is their core business. Amazon’s biggest revenue creator is their Amazon Web Services (AWS) arm followed by their incredibly vast and profitable retail entity. Disney is a well established studio with a massive theme park business that quite literally prints money. And Apple is the undisputed giant in the consumer electronics and tech space. Streaming and entertainment are vanity projects for them. Disney literally makes more money selling churros at their Orlando theme park than it makes from Disney Plus subscription fees (and the latter only turned a profit last year). Amazon could splurge a nine figure sum on producing a critically panned Rings of Power and the price tag for this production will be a rounding error on their end-of-year balance sheet. They can all afford to see their streaming arms lose fabulous amounts of money on attracting high-profile filmmakers and shelling out on licensing fees and they will all be fine tomorrow. Except for Netflix.

Netflix never had a fallback option. And now that at least in the developed world they are probably looking at reaching complete market saturation quite soon, they don’t have any more room to grow. And their streaming business needs to make money because they don’t have a billion dollar churro establishment or a culturally-entrenched smartphone they can sell you. Therefore, they are facing one of the possible routes ahead: (1) Growing through acquisition of their competitors and temporarily growing their share of the pie, (2) attempting to penetrate other markets which is a viable option but unlikely to generate sufficient revenue in short-to-medium term, (3) building or acquiring capability to penetrate the traditional production market, (4) diversifying their offering to enter other modalities like video game production, and (5) squeezing out additional revenue from their existing customer base through gradual “enshittification” of their services, like adding ad-supported tiers and raising prices of their standard package.

It’s easy to see that Netflix has been dabbling with all those options, as they have indeed introduced ad-supported tiers and increased their prices. This is likely a move aimed at enabling the penetration of emerging markets in India and countries where customers would be unlikely to pay the kinds of fees we are used to in the developed markets. They have introduced mobile gaming to their offering, presumably in an attempt to expand into other spaces and maybe to lay the groundwork for more substantial moves. Can they acquire one of the AAA game developers? Time will tell. But this latest move suggests that what they truly intend to do is to shift the core of the business away from streaming and towards the traditional movie production modality, which is known to generate money. What I think we might be able to see in the coming months and years is Netflix’s financial wellbeing becoming more dependent on movie production and distribution. We are probably going to see them generate revenue from bringing back physical media, which is something Disney reinstated recently as they saw that there is still a market in this space, especially when it comes to collectors editions and limited runs aimed at fans of specific IPs.

What I find particularly ironic about this announcement is that it looks to me as though Netflix executives finally realized that the business model they disrupted with the introduction of their SaaS-like subscription model never had legs and its longevity had a rather short runway. It was profitable as it grew, especially in the absence of serious competition, but now that the market has saturated, it is clear that the real money was always to be made old school. Thus, with their acquisition of Warner Bros Discovery, the disruptor has become the disruptee. And because they never had another reliable revenue generator to fall back on, this glowing announcement might be nothing more than an admission that there was nothing wrong with the way movies were made, distributed, exhibited and profited from in the pre-Internet era. It might just be that Netflix did not destroy the old model. They simply delayed discovering why it existed.

Leave a reply to Netflix at a Crossroads, Disruption as Religion and Red Flag Messaging – Flasz On Film Cancel reply