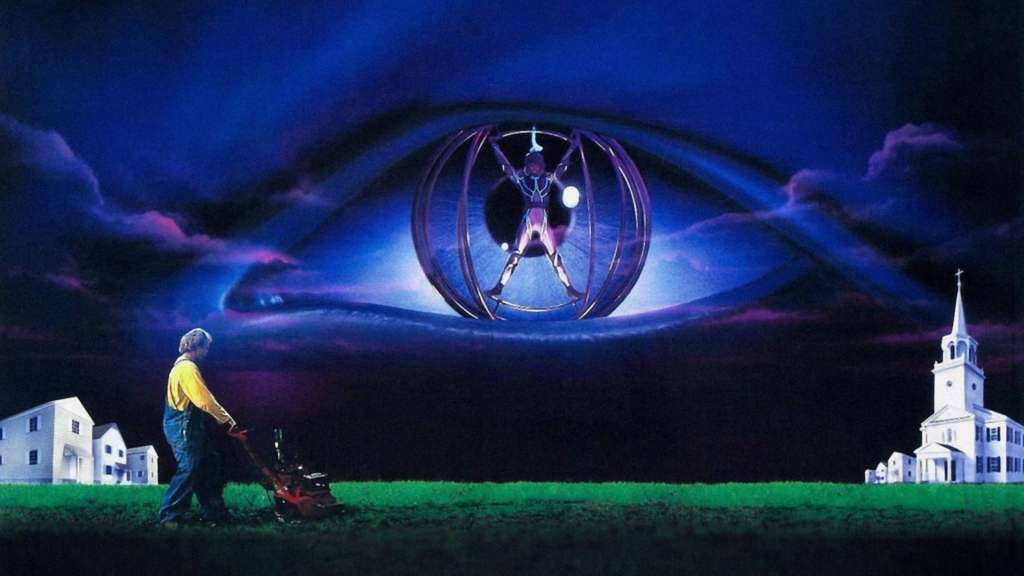

If you had the fortune—or misfortune, depending on your outlook on the fact it was north of three decades ago and that it might or might not signify you’ve got less life ahead of you than you have in your rearview mirror—to be around during the video store era, you may remember scanning through the many colorful VHS covers and coming across a little old movie called The Lawnmower Man.

An ominous-looking piercing eye, a blob of heavens-knows-what that you may now recognize as an early attempt at CGI effects and, down at the bottom of the image, a man in dungarees mowing a lawn. ‘What could this movie be about?’ you whispered to yourself as you took the box off the shelf and turned it over. And if you were lucky enough, you’d be greeted with a blurb announcing the movie was “based on a short story by horror creator Stephen King” right after introducing you to Pierce Brosnan as a computer scientist Dr Lawrence Angelo and Jeff Fahey as a simple gardener whose brain capacity is increased by 400% by the powers of virtual reality. Or something. Look, we didn’t have Wikipedia back then and the Internet was mostly a scientific experiment in its own right. Therefore, unless you have read the short story this blurb was suggesting as the basis for the movie titled The Lawnmower Man, you had no other recourse but to take this information at face value. Which is what many people did.

We all sat down and watched the movie where Pierce Brosnan plays a suave scientist with a god complex and Jeff Fahey does such a great job playing into stereotypes concerning people with developmental maladies that if this movie had been bankrolled by Disney and streamed on its proprietary platform, it would have most assuredly been accompanied by a title card informing the modern viewer of the fact the movie reflects outdated stereotypes and it may in fact be a product of its time, or something to a similar effect. We watched it and assumed this cyberthriller about chimps playing first-person shooters and disabled gardeners gaining superhuman abilities by having parts of their brains unlocked for them by smug scientists wearing criminally underbuttoned shirts—think of it as an early protoplast of Luc Besson’s Lucy if it strikes your fancy—was written by the same guy who gave us Carrie and The Shining. Some of us may have even picked up a copy of Night Shift, the 1978 short story volume in which The Lawnmower Man was collected after its initial publication in the May 1975 issue of the Cavalier magazine. But only those who read the story knew the real truth. That the movie had absolutely nothing to do with King’s story. Like, at all.

I often wonder what the limit of an adaptation is and where are the boundaries of creative licence for making changes to the source material one is working on while translating anything from the written word into material suitable for cinematic treatment. How far can you push before the movie you’re making becomes completely detached from the source material? What are you allowed to mess with before the integrity of the original story is irreversibly altered and the author becomes audibly displeased about whatever it is you have done to their creation?

Look, there are no easy answers to these questions, and they surely vary from person to person. And even as far as Stephen King is concerned, the evidence shows that he has been considerably more amenable to having his work messed with when it came to his short stories, while he remained more precious about his novels. However, this here is a great example of what happens when someone in the film production space goes into a hold-my-beer-and-watch-this mode and decides to adapt a book without even reading it first.

The Lawnmower Man, as written by Stephen King, was nothing more than an innocent vignette. Adapted for the screen, it would be a rather quaint and unobtrusive genre piece with a bit of a pun festooning its tail end. In fact, it was adapted verbatim thanks to King’s Dollar Baby initiative which allows indie filmmakers to take on his short stories having paid the author a symbolic buck for the rights. The short is exactly what you imagine it would be—rough, but for the most part unobtrusive and mostly unmemorable. It concerns a guy who finds a mowing service in the paper and finds out the lawnmower man has hoofed feet, mows the lawn in the nude and the lawnmower he uses is somehow autonomous. Well, it’s powered by magic because the hoofed lawnmower man in the nude works for the god Pan who presumably grants him some magical powers. Oh, and he eats the grass trimmings coming out the back of the mower. And when our guy, Harold Parkette his name, decides it’s in his interest to call the cops because it is after all a strange occurrence to have a nude man run on all fours behind an autonomous lawnmower while gobbling up grass trimmings, he gets mauled by the lawnmower, Dead Alive style. The end.

Anyone who read the story and heard there was a movie titled The Lawnmower Man would probably expect something that would vaguely resemble the outlined narrative. Granted, I don’t know how you’d turn it into anything longer than a fifteen-minute joint in an episode of Tales from the Crypt, but that’s not really my problem. But as you may imagine, a lot of people expended considerable effort trying.

Now, to the best of my understanding of the matter, the rights to Night Shift in its entirety were purchased initially by Milton Subotsky and Andrew Donally in 1978 and then sold to Dino De Laurentiis who planned to use adapt these short stories into a series of anthologies beginning with the 1985 Cat’s Eye. I think he may have later changed his mind and thought it’d be cooler if all those stories were made into standalone movies, beginning with Maximum Overdrive. Well, I don’t think De Laurentiis had a great time working with King on that project given the many problems reported during the production, starting with King’s allegedly perpetual state of inebriation and ending with a handful of serious accidents on set resulting in life-changing injuries to the cinematographer, to name but a few. A production outfit called Allied Vision acquired the rights to The Lawnmower Man in pursuit of turning it into a standalone movie anyway, but—let’s just say unsurprisingly—struggled to turn it into a workable script. Because, how exactly? You can’t really stretch it, there’s not much room to pad it out with lore, so you honestly have to make stuff up to turn it into a feature-length affair. Which is what happened.

At the same time, Brett Leonard (who ended up directing The Lawnmower Man) and Gimel Everett were working on a script titled Cyber God about a scientist working on virtual reality to unlock untapped abilities of the human brain. And someone somewhere thought it’d be a good idea to somehow hybridize the two projects and turn it into one movie. But how do you fit a Pan-worshipping nude guy eating grass and a flesh-eating autonomous lawnmower into a story about a scientist teaching chimps to play Doom in VR? Well, you have to get rid of something, so they decided to ditch the content of King’s story wholesale… leaving only the title because it either rolled off the tongue better than Cyber God or because they felt they needed the title to preserve the idea of actually still adapting Night Shift into a series of standalone movies while forgetting that the movie they were making had literally nothing to do with the story they had allegedly intended to adapt.

However, it’s not exactly true that the filmmakers in charge of putting The Lawnmower Man together ditched King’s story entirely leaving only the husk of the title and an attempt at leveraging Stephen King’s brand. If you look closely, you will see that they left enough material in the script to successfully suggest the title isn’t coincidentally the same. The movie does have a character of Harold Parkette, a beer-chugging brute in this guise, who also gets turned into mince by a lawnmower telepathically operated by Jeff Fahey’s character. Plus, there’s at least one or two mentions of a sinister government outfit called The Shop, which features in Stephen King’s Firestarter, so nobody could ever pretend they weren’t working with Stephen King’s material and that all resemblance of characters and ideas is merely incidental. It wasn’t. They took King’s story, gutted it so hard that only the title remained, but they felt they needed some connecting tissue tethering them to King’s work, so they left those few blink-and-you-miss-it Easter eggs in the narrative. Which is bizarre and, as it turned out, disrespectful to the author so profoundly that he sued the production and had his name disassociated from the production in every way.

And even having won the case and likely secured himself a nice little settlement for his troubles, poor old Stephen would remain forever associated with this movie. This is partly because, as I alluded to in the opening paragraphs of whatever this is—I don’t know, a pseudo-analytical rant about what happens when the limits of artistic licence are probed by those who might not have known any better—King’s name featured for a little while in quite a few jurisdictions on the VHS cover of the movie. And to be perfectly frank, even if it hadn’t, The Lawnmower Man would forever remain associated with him despite the fact the movie has absolutely nothing in common with the story it is allegedly inspired by. A genie cannot go back to the bottle. Once gossip is out there, it’s out there forever and this had been true long before social media and the modern incarnation of the Internet turned everything into a permanent record of reality: the truth, the facts, the lies, the half-truths, the fibs and everything else in between. Once it’s out, it’s out. And as the adage goes, a lie is halfway around the world before the truth has put its trousers on. So, there.

Or maybe it is simply a testament to Stephen King’s unique brand because for a good while back then—and perhaps even today—he had been Hollywood’s cash cow. He’s the guy whose work you can adapt ad infinitum, remake, reboot, sequelize and prequelize. Sure, it might not make any money or sense whatsoever, but as long as a movie is even tangentially related to King’s work, it’ll never be truly forgotten. You don’t have to look very far for evidence of that. Think of those sequels to The Mangler which nobody should ever think of watching. They’re not even remotely related to the original story (and in Tobe Hooper’s defence, the original was at least somewhat related to the short story) and the one titled The Mangler 2: Graduation Day has more in common with the movie The Lawnmower Man than the movie The Lawnmower Man has to do with anything King ever wrote. But you can easily find it on YouTube because there’ll always be someone who wants to watch a movie even distantly related to Stephen King’s work. And that’s why we have The Lawnmower Man instead of Cyber God, which probably would have been just as wacky a techno-thriller. Maybe it would have survived on the back of its own merit because the movie does feature some interesting early examples of CGI, and it also touches on themes that only in recent years have become truly intriguing, especially when you drag its sequel Lawnmower Man: Beyond Cyberspace into the conversation. Quite frankly, those two movies together with stuff like Tron, World on a Wire and Ghost in the Shell have become the runway for movies like The Matrix, Paprika, or more recently The Creator while also remaining tethered to such (mostly forgotten) duds like Transcendence or Lucy.

But it has nothing to do with the short story and the fact it exists proves just how far into absurdity Hollywood producers are willing to push things, even at the expense of angering one of the most successful writers of all time. And as it turns out, you can in fact adapt just a title of a book and replace nearly all of its narrative content, for what it’s worth.

Leave a comment