The longstanding, widely accepted genesis of Stephen King’s The Stand is that it was supposed to be his The Lord of the Rings, an epic fantasy adventure with the highest stakes possible and numerous characters placed in what was then a contemporary American setting. And even though this statement is true insofar as it is every writer’s dream to put together a piece as incredibly resplendent, intricate and accomplished as J.R.R. Tolkien’s magnum opus, its beginnings are quite a bit humbler. And also, in contrast to Tolkien’s seminal piece of high fantasy, what makes The Stand unique might not be its sprawling ambition either.

In fact, King didn’t intend to write The Stand in the first place and instead, having delivered Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot and The Shining, he was working on a novel about the kidnapping of Patty Hearst and her subsequent brainwashing (or political awakening, depending on who you’d ask). He lived in Boulder, Colorado—which as you might know, later became one of the two major nexuses of the story in The Stand—and one day learned about a dangerous chemical weapon spill in Utah, which thankfully only wiped out some sheep. But if the winds had blown in the opposite direction, a local town would have suffered mass fatalities, so it definitely qualified as a close call.

Interestingly, the incident itself served as a basis for a movie Rage starring George C. Scott, but what it did give Stephen King was the activation energy required to turn his Patty Hearst book (tentatively titled The House at Value Street) into something else entirely. Having suffered for months trying to tackle this piece of based-on-a-true-story storytelling and having committed all those attempts to the cavernous oblivion of his personal wastepaper basket, he visualized Donald DeFreeze, the leader of the radical left faction responsible for the kidnapping, as “the dark man.” And having recalled George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides (and most assuredly also Richard Matheson and Jack Finney whose ardent champion King has always remained), he gave himself the central what-if scenario needed to launch what later became The Stand: what if a weapons-grade virus escaped the lab and wiped out 99% of the world? What would happen to the survivors?

What King did not know at the time was that he was signing up for what he later referred to as his own personal Vietnam because the book didn’t seem to want to come to a close. Every time he thought he’d be getting to a conclusion of sorts, he’d add another one hundred pages to the pile. It took him over two years to finish the job. Under normal circumstances, completing a manuscript would take Stephen King a few months tops, as he has always been a prolific and disciplined writer who religiously typed two thousand words a day. Not this time, though. Writing The Stand took a toll on him and he’d later jokingly remark that he dreamed about dying of a heart attack in the middle of the street while attempting to deliver the manuscript to his editor personally.

By the way, there must have been something in the water in the late1970s as many era-defining artists also embarked on projects that would come dangerously close to ruining their lives. Francis Ford Coppola decided to adapt Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness into Apocalypse Now, Michael Cimino went on to make Heaven’s Gate, William Friedkin staked his career on Sorcerer, Fleetwood Mac recorded its sprawling and experimental double album Tusk. Norman Mailer wrote The Executioner’s Song, a brick-sized true-life novel about Gary Gilmore that nearly broke him. Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, although published in 1973 thus flying in the face of my half-baked theory here, forced the author into self-imposed exile for nearly two decades. It was a time for great people to bite more than they could chew.

In fact, when The Stand finally came together, at twelve hundred pages it was deemed unpublishable by bean-counters at Doubleday. Because King worked in genre and his work was at the time seen exclusively as entertainment rather than literature, the job of his books was to make money. And the calculation was that for The Stand to bring a profit at a price point the publishers thought that the market could cope with, the book could not be longer than eight hundred pages. Otherwise, production costs associated with printing and binding such a large tome would either force the price above what the public was willing to pay, or Doubleday would have to publish it at a loss.

Hence, King was told that a third of The Stand had to be edited out, which is a politically correct term for what you’d otherwise see as an act of brutal evisceration. The author did the gutting himself, and it took another ten years for The Stand to be re-published in a form that was closer to what King intended originally with updates to the temporal setting and changes to cultural references that would have been out of step with the time.

However, this is also where the book developed its weird tone. No. Hold on. I tell a lie. When published as a hardcover at the tail end of the 1970s, The Stand was set to take place in 1980, which was supposed to translate in the imagination of the reader to “not too distant future.” The paperback release, though, moved the timeline by five years and the arrival of the deadly Captain Trips virus was then supposed to happen in 1985. When King sat down to rewrite the book into its “complete and uncut” edition, he decided to push the events further and set the book in 1990. Appropriately, this time he went through the book with a fine-tooth comb and replaced all musical and movie references with ones that characters living in the late 80s would be more at home with and called it a day.

But the problem is that scrubbing references to The Eagles and replacing them with Depeche Mode was not enough because the characters using those references for the most part remained unchanged. And this is where sometimes King’s ingenious knack for creating lifelike characters out of thin air might become a double-edged sword because although these people were talking about Madonna and 80s television, they still talked and behaved like people plucked out of the 70s. Although mostly subtle—except for the entire character of Larry Underwood whose singer-songwriter character defined by rock-and-roll hedonism and latent narcissism screamed the 70s—these idiosyncratic anachronisms made The Stand into something quirky and perhaps incompatible with cinematic adaptation.

At the same time, The Stand looked and felt like a story that begged to be transplanted into the medium of film. After all, thanks to King’s aptitude for crafting incredibly cinematic scenarios filled with characters you’d want to meet or at least experience in person—granted, I wouldn’t want to meet Randall Flagg at all if I could help it, thank you very much—combined with the sheer volume and scale of the story, The Stand felt grand and deserving of such treatment. That feeling of organic grandeur is in no small part owed to the fact that King introduced its dark fantasy core through the back door. This might be a byproduct of his writing process as well, as he’s known for letting the characters do their thing and flying by the seat of his pants while writing.

Thus, it’s impossible to accuse the book of “knowing” the direction it was headed because the author was figuring out where it wanted to go as he went along himself. It still started with King’s familiar what-if setup of what would happen to the world if a virus wiped out most humans and only over time transmogrified into something different. In fact, this is where the genius of The Stand truly comes to fruition because it does not originate as a work of high fantasy and lures the reader into its sprawling opera with a post-apocalyptic slant. You could probably make a movie out of the first part of the book all by itself because the concept of a deadly virus escaping a lab and a bunch of survivors attempting to reform a working society out of the ruins of the old one would be good enough.

What distinguishes The Stand from stock post-apocalyptic dystopia is that, slowly and methodically, as it allows the reader to saddle in and develop some fundamental familiarity with the post-pandemic setting, the wholesale societal breakdown and the cast of survivors navigating this predicament, it trickles in its fantasy in small doses. Here and there. A bit at a time. It takes a while for Randall Flagg to be introduced as more than a simple agent of chaos and for Mother Abagail to become his antithesis, and even more for the book to adopt an overtly fantastic tone wrapped tightly in Judeo-Christian iconography. By the time the reader realizes that The Stand has become a piece of dark fantasy woven using cultural threads native to the Western civilization, it’s impossible to put the book down. By then we cannot help but see things through and find out how Stu, Frannie and others come out of what clearly shapes up to become an apocalyptic encounter with Satan himself.

What starts as a piece of post-apocalyptic survivalism ends in a flurry of Christian magic and an epic stand-off between canonical forms of Good and Evil of biblical proportions and tone and it is only rendered possible because of the volume and scale of the book. This is not something one can condense to a mere few hours of visual storytelling. The Stand has always thrived as an experience that displaces the reader into its world for weeks, which also normalizes what otherwise would come across as a tonal shift of unreasonable proportions. When the Trashcan Man wheels in an A-bomb into Las Vegas and the literal nest of sin ends up vaporized after what can only be seen as a divine intervention and a small handful of miracles, the reader has been at home with such a fantastic resolution because King has built up to it over the course of enough pages to satisfy the requirements of two bog-standard page-turners.

This presents a terrible dilemma as far as adaptation is concerned because The Stand requires those who choose to do it to both heed its need for scale (which comes with associated production costs) and reckon with the fact that it cannot be made a into single three-hour film. In fact, it doesn’t easily lend itself towards being transcribed into a trilogy akin to Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings either.

In contrast to Tolkien, who I believe was convinced by his publisher to break up his oppressively large piece into three volumes, King did no such thing. Instead, as I remarked above, he was asked to disembowel it. But when the time came for the rubber to meet the road—after nearly a decade of tussling in the development hell—The Stand had returned to its original scale and size. Perhaps when George A. Romero was attached to direct it in the 80s, there was a way to pare this story down to fit within the parameters of a single movie you could sit through without developing bedsores but come the 90s the landscape had shifted. After WB had backed out of the opportunity to turn the book into a single three-hour movie, the only recourse was television.

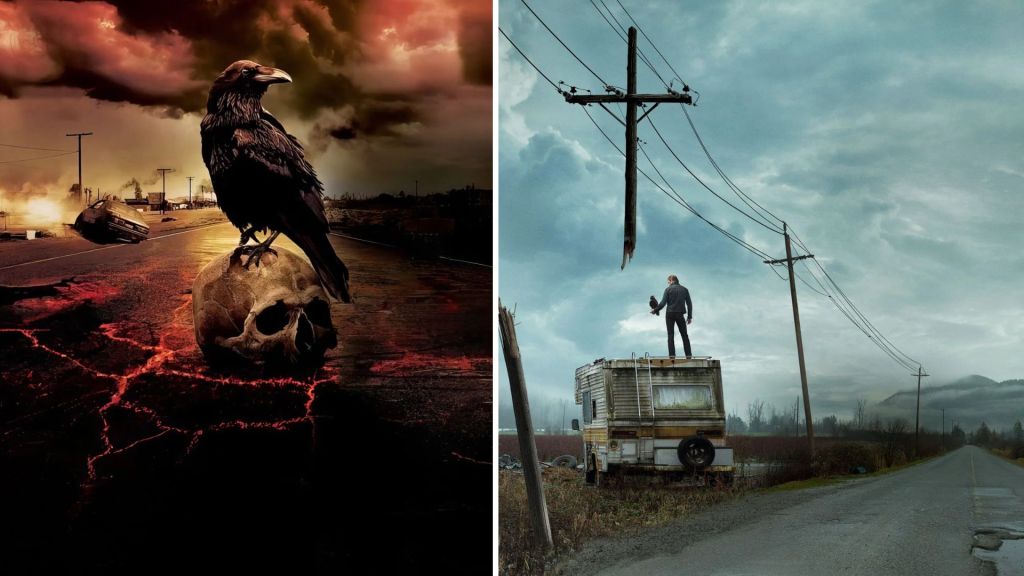

ABC asked King to turn The Stand into what became a three-part eight-hour miniseries, for which the author penned the screenplay. Mick Garris was hired to direct, perhaps in the wake of his previous collaboration with King on his original story titled Sleepwalkers. The two would go on to collaborate on several other occasions, as Garris would later direct the miniseries version of The Shining, Desperation and Bag of Bones.

Garris, bless his heart, is one of those guys who has always approached King’s texts with almost religious deference and for the most part executed exactly what was on the page, cap in hand. Which is all OK because The Stand was written in such a way that it could be translated verbatim into cinema and it would still work. The problem was that with a long list of cast members like Gary Sinise, Rob Lowe, Molly Ringwald, Laura San Giacomo and Miguel Ferrer, nearly nine hours of running time, multiple settings and special effects, the budget of twenty-six million dollars wouldn’t go very far. Therefore, despite the fact it has many fans to this day, the 1994 adaptation of The Stand honestly fails to capture the epic tone and scale of the book and instead, it frequently veers towards camp.

What it does well, however, is the way in which it unapologetically and unambiguously anchors itself in Christian mythology in which King had steeped the novel. Even with his Canadian tuxedo getup—head-to-toe in denim for those unable to google—there was no debate that Randall Flagg (Jamey Sheridan) as adapted by King himself and visualised by Garris was clearly a personification of the same devil that tempted Eve to eat the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. Unfortunately, the 1994 adaptation just didn’t have the oomph to take the viewers on a journey that could be compared to Frodo’s quest to dump the Ring of Power into the fires of Mount Doom. It was a soap opera with shoddy special effects that suffered from severe pacing issues and author’s own separation anxiety. King and Garris didn’t have the money or the necessary grasp of cinematic vision to transcribe what millions of readers could easily project in their Kopfkino while reading The Stand into a work of high fantasy sneaking through the backdoor left ajar in the house of post-apocalyptic survival horror.

Attempts to adapt The Stand never ceased even though the 1994 Garris-King effort grew a cult following in the years following its original broadcast. It was obvious to everyone that regardless of fan reception, King’s opus had not been done justice. And it doesn’t even matter that the author himself had been involved in the process. It honestly doesn’t factor into whatever legitimacy this adaptation would carry. It either works or it doesn’t. In contrast to Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, which has become a nearly untouchable masterpiece, and we might have to wait a long while before another adaptation is attempted, The Stand kept percolating on the lips of producers and keen screenwriters for years. In fact, the success of Jackson’s take on Tolkien might have briefly reinvigorated this topic in the late 2000s as a multi-movie adaptation went into development with David Yates at the helm.

After some tossing and turning, Josh Boone ended up stuck to this project which was briefly shaping up to become a four-movie affair, reflecting the structure of the novel. Stars like Ben Affleck and Matthew McConaughey were attached for one hot minute but appetites waned eventually. It seems the post-Jackson trilogy boom bolstered by the incredible success of the Harry Potter series (which sustained a multi-sequel franchise itself) was not enough to give The Stand a landing zone.

When the swelling success of cable-ready anthology miniseries emboldened by the disruptive force of streamers and their binge-friendly release formatting, the four-movie adaptation morphed into a miniseries capped with a movie before fizzling out completely. It took another handful of years before CBS All Access picked up King’s novel for a ten-hour miniseries, for which King rewrote the ending and engaged his son Owen in a writer-producer capacity.

Lessons have been learned and instead of transcribing the book page by page, the 2020 The Stand, filmed right before the COVID pandemic—our own Diet Captain Trips—made landfall, Josh Boone and his co-conspirators decided to lean into the fantastic elements more overtly and immediately. In fact, the 2020 adaptation dispenses with the novel’s timeline and feeds the pandemic chapters in between what it sees as the story proper, which sees the characters already either en route to or settled in Boulder. This fixes the glaring pacing issues present in the Garris adaptation from 1994, but at the same time it completely overlooks King’s backdoor fantasy introduction. It’s no longer a story about a world disrupted by an outside force and then morphed into the American equivalent of the Middle-Earth. We’re in the fantasy from the get-go. There’s no debate that Randall Flagg is a supernatural character. Magic and destiny are foundational aspects throughout this miniseries rather than revelations to be made on the way.

Again, this is OK as far as artistic choices go, but as with everything, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. The mystique of the novel and the incredibly compelling method of unraveling its world cannot coexist with the way events are presented here. However, thanks to the fact that in the intervening twenty-six years TV has become more accommodating towards mature material, this omission could be compensated by allowing the viewer to experience the scale and nature of Flagg’s threat more overtly. The miniseries is more violent and suggestive than the Garris adaptation, which definitely helps.

However, at the same time it also looks as though the book’s overt Judeo-Christian connotations have been curtailed and hidden within aesthetic ambiguities. While Jamey Sheridan’s Flagg was most definitely a demonic presence with a physical form to match, the same cannot be said about Flagg as depicted by Alexander Skarsgard, who throughout the bulk of the series is characterized as more of a warlock, a human with supernatural powers instead. It is as though the filmmakers worried that the book’s earnestness in rooting its fantasy in Christian mythology would come across as unfashionable. It’s there but severely underplayed.

As a result, the 2020 adaptation, despite its new ending where Frannie and Stu end up squaring off against Flagg in a battle of wills after Las Vegas disappears off the face of the planet, the entire project has an underwhelming aroma to it. A whiff of non-committal. You’d think that while we were sequestered from the outside world by a malicious invisible threat of a virus that also, as it turned out, most probably left a lab glued to someone’s shoe, this ten-hour epic adaptation of The Stand would have fit right in. Unfortunately, it did not. Maybe it’s the timing. Maybe it’s the fact that despite being an improvement in terms of scale and ambition, it still fell short of what King’s novel succeeded at so effortlessly.

Perhaps The Stand is simply unadaptable into a successful cinematic piece without someone taking a risk and leaning into its earnest mythologizing and trusting the process of introducing its fantasy in small portions. It’s a piece that needs epic scale that cinema affords and patience most often found on the small screen. Normally, these two approaches would be at odds with each other. Twenty years ago, the solution to this problem would have been a cinematic quadrilogy built on a foundation of a generous budget and star power of its leads. Now, it seems the way to go is to follow the logic of Rings of Power and spend just as much money on a production intended for binge-watching at home.

Much like Randall Flagg at the end of the book, the perfect adaptation of The Stand is still out there, waiting to reveal itself. The word on the street is that Doug Liman is working on a movie adaptation himself. My personal opinion is that if this does not turn out to be a trilogy in the making, we might have to wait some time longer for a worthy attempt. Unfortunately, we have now been conditioned to expect The Stand to be fit only into the confines of a miniseries and I’d like to see this myth dispelled. King wrote an epic fantasy that sneaks up on the reader and deserves to see it adapted with appropriate flair and grandeur. My watch hence continues unabated.

Leave a comment