All throughout his career, Richard Linklater remained married to the idea of experimentation. Together with Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino and others, he charted his path through what we now refer to as the 90’s Indie Revival by committing to formally intriguing projects like Dazed and Confused or Before Sunrise which fit quite well within the zeitgeist of dialogue-heavy hangout experiences with a well-developed cool factor. But even though he could always find a niche for himself within the movie industry, Linklater has always managed to fly just a few inches under the radar while periodically emerging with movies that grabbed the attention of critics (Boyhood, Before Midnight) but rarely moved audiences; though, School of Rock is probably a great example to the contrary.

He never had a movie like Pulp Fiction or Boogie Nights that would cement his stature in the mainstream, nor did he pull a studio juggernaut like Ocean’s Eleven out of his hat. But in contrast to many of his peers, he never stopped playing with the form. Like Steven Soderbergh, Linklater remained prolific and committed to keeping the audiences on their toes. Truth be told, every new movie he directs is always at least a little bit surprising because he never truly settled into a stylistic groove like Tarantino, or Paul Thomas Anderson.

Which is why the idea of him setting out to direct a movie that chronicles the production of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless starring predominantly French actors and filmed in a style evoking the French New Wave filmmaking sensibilities is in many ways a perfect reminder of Linklater’s place in the pantheon of stalwarts of The Great Indie Revival from which he originally hailed. What I think he achieved by committing to a project that clearly counts as off-kilter as far as the expectations of mainstream audiences are concerned is that he could both reconnect with the era of moviemaking whose banner he has helped to carry throughout the years and remind the world at large of his own importance as an innovative and fundamentally radical visual storyteller.

Nouvelle Vague reminds me a lot of Soderbergh’s The Good German (an experiment in making a 1940’s movie sixty years later) or Kafka (a meta-experiment in bridging Orson Welles and Terry Gilliam) in that it attempts to function as an exercise in a strictly controlled style, but it does so for more than just its own sake. It’s equally a love letter to Godard and Truffaut—the patron saints of the kind of cinema 90’s indie mavericks espoused—as it is a gateway drug aiming to demystify their movies, which might come across as impenetrable to modern audiences. We mustn’t forget that a movie like Breathless, The 400 Blows or Hiroshima Mon Amour are just as culturally alien to a twenty-year-old film fan looking to widen their horizons now, as Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons and Maltese Falcon would have been to someone like me when I was that age.

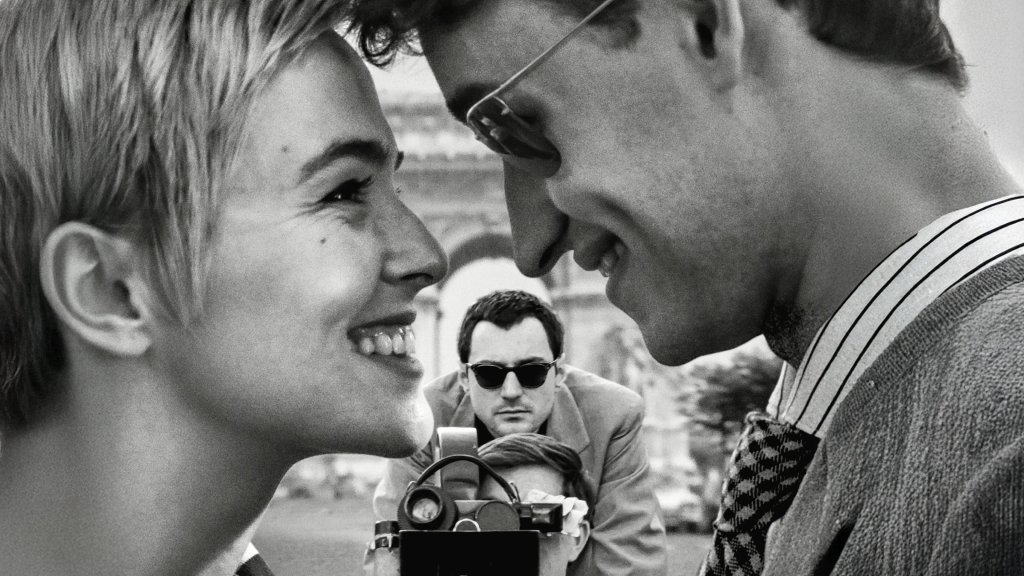

What Linklater achieves here is that he decodes the subversive style of those 1960’s wild cats by both showing and doing. Similarly to what I think Godard and Truffaut would have done having embarked on a project like this (though they would have probably made movies about how Hitchcock made Shadow of a Doubt instead) Linklater leaves very little room for artistic deference towards these great trailblazers and instead invests nearly all his energy into crafting an experience that will educate the viewer on just what it meant when these French movies were being described far and wide as revolutionary and radical, while also looking like one. Nouvelle Vague then, methodically yet without coming across as didactic or sequestered from the story, reiterates that using small handheld cameras typically deployed in news reportage and war correspondence to make a feature movie was just unheard of. Equally, the filmmaker weaves the bulk of narrative tension around the ceaseless friction between Godard (played here by Guillamme Marbeck) and his producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfurst), who wasn’t prepared for the maverick director to casually defenestrate decades of tradition and custom in filmmaking procedure. The same goes for how everything seemed written on the fly—even though they did have a script and a shooting schedule—because Godard wanted his actors to be natural in how they responded to his direction, which he dispensed casually from behind the camera in real time while dollying his cameraman in a wheelchair. This particularly annoyed Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) who was used to difficult filmmakers like Otto Preminger but not quite to iconoclasts bent on shooting movies like rogues: on location, in tight spaces, without permits and without rehearsing.

At the same time, Linklater also denudes somewhat the inflated status of Godard as a god among men. He portrays the guy as a quipping machine who spoke nearly exclusively in quotes from other artists and overgrown personalities and sounded frequently like a walking and talking bumper sticker. However, the way he does it is what matters because through Linklater’s lens, Godard isn’t real but rather a New Wave approximation of itself, a persona personified; a brand characterized. Therefore, the movie assumes the form of a weirdo Möbius strip that folds upon itself formally. It’s a New Wave movie about the New Wave that deconstructs the New Wave using New Wave tools. It’s a movie about how Godard decided to deploy jump-cuts to discombobulate the sense of temporal progression in which jump-cuts do the same to its own narrative. This way, the filmmaker has a unique opportunity to teach his audiences about these filmmaking concepts in the most compelling way: by doing.

Consequently, Nouvelle Vague adds up to a thoroughly enjoyable movie experience that entertains and educates in equal measures while also illuminating a few things about Richard Linklater’s place in all this. He has long been seen as that guy who loves meddling with the passage of time, which is true, but this is merely an outgrowth of his wider interest in sculpting freely in the filmmaking form. And this is something he most certainly picked up from the New Wave guys. They indulged in making movies out of sequence and out of sync while nobody knew it was possible. Sure, it’s much more difficult to innovate on this scale now, but I think a movie like this should also serve as an instructive reminder that that guy who keeps revisiting the same couple every decade, made the ultimate coming-of-age drama by capturing a real process of a boy going through adolescence and frequently deploys modalities like rotoscope animation when it suits his mission is a de facto descendant of these bozos who roamed the streets of Paris and made cool movies.

This movie will also count as a repository of off-the-cuff trivia and a bag of catnip for any film fan. We get to wander around town with Godard in his sunglasses as he bumps into Robert Bresson shooting Pickpocket, visits Jean-Pierre Melville’s set, supports his buddy Truffaut whose debut The 400 Blows was pummeling the stale zeitgeist and gets told in no uncertain terms by Agnès Varda that the most important aspect of his decision to direct a movie—which he saw as a massive existential burden because he was about to put his money where his critic mouth was—was “not to fuck it up.” However, these tidbits never overwhelm. They’re here for you if you want to explore them, like pieces of throwaway commentary with which Godard would saturate nearly all of his movies from that era, from Breathless and Band of Outsiders to Week End and many others.

Taken together, Nouvelle Vague is a treat to watch. It might not be the best movie of the year, but it ranks up there with the most easy-going and enjoyable experiences. It is equally an Easter Egg hunt for movie nerds and an intricately built experiment in meta-storytelling that is both of and about the French New Wave. Linklater once again delivers a movie that enriches and ensnares with his inclusive atmosphere and an inviting tone of an avid student of the filmmaking tradition and a curious fan of hanging out and watching movies together. Contrary to Godard who quickly traversed into the realm of self-indulgence and pretentious self-aggrandizement, this filmmaker can radically sculpt in the filmmaking form and draw attention to his style while remaining authentic and inviting. Which is probably why I might now recommend Nouvelle Vague as a calibrating pilot experience to begin a journey through the French New Wave. I’d be hard pressed to find a better entry point that would tell anyone how these movies ought to be watched without sounding snooty and academic.

Leave a reply to BLUE MOON and the Mystique of Quietly Radical Anti-Biopics – Flasz On Film Cancel reply