The concept of a sequel is as old as cinema itself, that’s without question. As early as the 1910s we saw plentiful examples of filmmakers recognizing the importance of brand familiarity and driving to bring in front of audiences more adventures from their favourite characters, like Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan or Captain Nemo. The idea of serialized entertainment was adopted almost as quickly (Fantômas, Judex, Les Vampires).

In fact, movie entertainment thrived for decades on long-standing series and franchises, like the classic Universal Monsters, Laurel & Hardy movies, series about James Bond and Godzilla, both of which continue to this day and remain some of the longest-running franchises in existence. However, the idea of adding numbers and subtitles only showed up over time. Sure, some early silent serials did sport numbers, and a few foreign movies were retitled when released internationally, but at least as far as Hollywood filmmaking is concerned, the widespread adoption of numbered sequels can be reliably traced back to the early 1970s (The Godfather Part II, The French Connection II and others) while the canonical subtitle gained in prominence in the early 1980s (Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior, Amityville: The Possession, Missing in Action II: The Beginning and many others). What’s worth noting is that at the time many subtitled sequels used dashes instead of colons. The latter was adopted much later and for the most part throughout the 90s and the early 2000s it was used in standalone films like South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut or Tom & Jerry: The Movie. The deployment of colons in sequels was yet to come.

It’s honestly a fascinating exercise to trace the last thirty-or-so years to see how the landscape of mainstream entertainment shifted over time. It’s not a big secret at all that in times of economic uncertainty, risk-averse decision-making most assuredly influenced the box office. Indeed, while in the 90s sequels reliably comprised 5-15% of the 50 most successful movies each year, things changed in the 2000s. Sequels gradually increased their presence to 15-25% in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble crash (e.g. The Matrix, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and others) and consolidated around 25-30% after the financial crisis of 2007-2009 (The Dark Knight trilogy, Transformers, the emergent MCU). Thanks to positive market feedback and continuing economic turmoil throughout the ensuing decade turbocharged by the relatively recent COVID pandemic, now in 2025 nearly 50% of the 50 highest-grossing movies at the domestic box office are sequels. That’s just the state of the game.

What’s particularly interesting about it is that we have to square two realities with each other: (1) that capitalizing on familiarity brings revenue much more reliably than investing in original ideas and (2) that sequels have historically been seen as inferior to original movies. After all, there is a reason why we continue to have debates about which sequel might be better than the original, which inherently assumes that the natural expectation is for the original to be superior. This is where the widespread adoption of a “coloned” subtitle (colonified? colonized? )came in handy to solve this little conundrum.

Back in the late 1970s and 1980s when Hollywood producers finally adopted data-driven approaches to market prediction, which included using focus groups and test screenings, as well as reliance on print and advertising to target specific demographics to ensure ample return on investment, simply numbering sequels was mostly good enough. In fact, after The Godfather Part II effectively legitimized the sequel in the eyes of the moviegoing community, many films spawned sequels and simply ended up with a number slapped at the tail end of it. Jaws 2. Rocky II. Halloween II. Many successful movies were immediately followed up with sequels, the vast majority of which failed to live up to the expectations set by their predecessors.

However, with movie series and franchises growing longer, the data suggests that while the first sequel in the franchise was almost certain to carry the number 2 (Arabic or Roman numeral, or sometimes something snazzy like a pluralization of the title or a play on words), the likelihood of a subtitle making an appearance increased to roughly 50% by the third instalment. In the 80s and in the late 2000s, a small exception could be made for movies that could capitalize on 3D projection by turning a 3 into 3-D (Jaws, Friday the 13th, etc.), but by the fourth sequel, the subtitle was nearly guaranteed. It is quite clear that Hollywood filmmakers felt that growing sequel numbers communicated decrease in quality.

What’s interesting here is that some long-running franchises remained mostly married to numbered sequels, with Rocky (later Creed) being the most prominent mainstream example. However, this phenomenon was mostly encountered in horror (e.g. Saw) and movies aimed at children (Despicable Me, Cars, Toy Story). The treatment of titles within the horror genre is particularly intriguing as it clearly seems that genre filmmakers cherished their series running well past five sequels and, in many cases, kept both the numerical and the subtitle. However, in mainstream franchises, the notion of a numerical sequel has been slowly but surely eroded, first by a numerical-subtitle combo, and now by a slick coloned subtitle and nothing else.

In fact, we now see more movies land in cinemas that carry a coloned subtitle despite not being a sequel, as though the presumptuous expectation behind such decision-making was that a franchise would sprout organically on the back of their success. Think Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, Warcraft: The Beginning, or King Arthur: Legend of the Sword. Neither of these films gained sufficient box office traction to generate momentum towards greenlighting a sequel and now they just sit there in the data with their colons exposed.

It seems that Hollywood moguls have found a way to camouflage the fact that nearly half of the box office slate is comprised of sequels, prequels and other franchise instalments (and for the purposes of this discussion, remakes have been left to one side) and now the vast majority of sequels hitting the screens carry a coloned subtitle. Some movie series like John Wick and Mission: Impossible have taken this idea to the next level by introducing chapters, dashes, extra colons and sub-subtitles while others like the Fast franchise truly abandoned all logic in doing so. The M:I series already has a colon in the title, which does present an aesthetic challenge. And also, the Ethan Hunt franchise has beautifully obeyed the rule seemingly present in the data as the numerical in the title ended up ditched exactly after Mission: Impossible III.

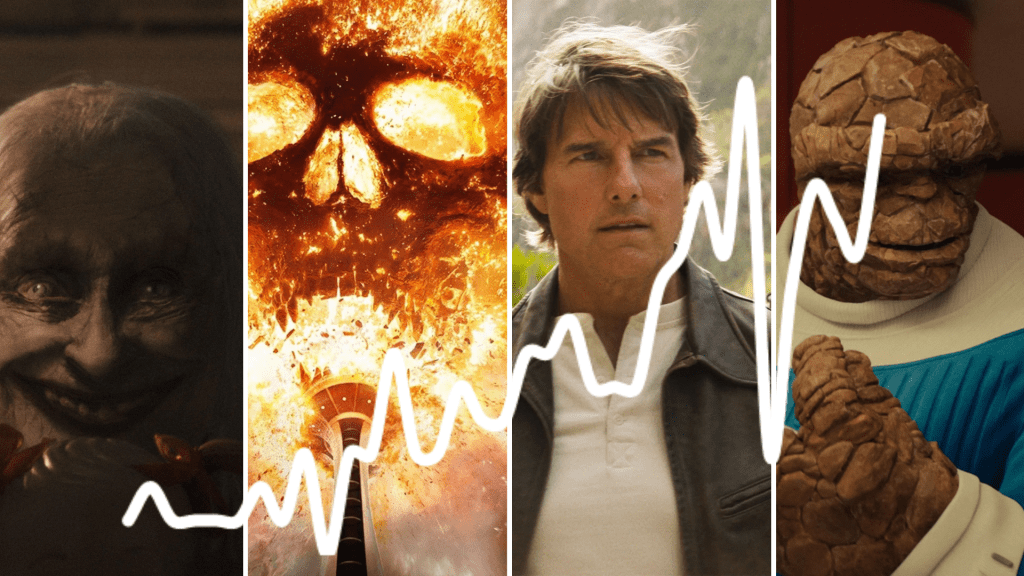

Admittedly, this notion gives movie franchises a certain degree of slickness because in conversation it’s way easier to refer to certain movies as Ghost Protocol, The Force Awakens or Wakanda Forever instead of trying to remember their number in sequence. But it does obscure reality and presents what clearly is a slate of numbered sequels in risk-averse franchises as plausibly novel. It’s not Fantastic Four 4, but The Fantastic 4: First Steps. Instead of The Conjuring 4 we have The Conjuring: Last Rites. We’ve got Captain America: Brave New World and not Captain America 4. Ironically by the way, even the first Captain America carried a coloned The First Avenger subtitle.

We all know these movies are not original and watching some of them requires extensive catching up—imagine waking up from a coma and deciding to watch a new Marvel movie completely blind—but their titles present a false conjecture that they are somehow standalone entities. Some of them are, while others are not. But the point is that they all belong in long-running series, many of which originated fifteen years ago or even earlier.

As a result, the true state of the current box office remains opaque because it’s not that easy to notice that half—half!!!–of the 50 most successful movies this year should have numbers beside their titles. If that were the case, I think we’d all be talking about just how risk-averse and lacking in originality the mainstream film entertainment has become over the years. We’ve gone from seeing 2% of the slate earmarked for sequels in the early 90s, and it’s only a matter of time before most mainstream releases will be branded franchise sequels. But you might not be able to tell immediately because their titles will have been completely colonized to obscure their true nature.

Leave a comment