Have you ever wondered why your body develops a tolerance to caffeine having discovered you now need to down three double espressos to make it through the day while years ago a small cappuccino would have kept you buzzed into the wee hours?

Caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist, which means that it blocks these receptors (mostly ones called A1 and A2A) from interacting with adenosine, one of the neurotransmitters responsible for the feeling of sleepiness and drowsiness. Adenosine concentrations in various parts of the brain fluctuate throughout the day and gradually increase towards the evening, which means that there are more of these molecules around to find their receptors and interact with them, thus contributing to your feeling of tiredness. As you sleep, the concentration drops and adenosine clears from your system, allowing you to feel refreshed and recovered in the morning.

When you introduce caffeine into the system as a competitor to adenosine, the short-term effect will be that caffeine will block this receptor and as adenosine builds up throughout the day, you won’t feel tired or sleepy until caffeine is cleared (which translates to a sudden energy crash) or until adenosine slowly outcompetes caffeine at the receptor (you end up feeling tired much later than usual). But your body isn’t stupid and since every action elicits a reaction, to counteract the newly formed habit of introducing caffeine to your brain in pursuit of keeping your energy levels higher for longer, your brain will gradually develop new adenosine receptors. And when there are more receptors to fight over, more caffeine will be required to see an effect.

There are many more similar feedback loops in our brains, though admittedly they are oftentimes much more complex than the relatively simple caffeine tolerance mechanism, but they principally operate in roughly comparable manner. For instance, our tolerance to watching horror films, which is a combination of neurochemical habituation and emotional desensitization, might be understood similarly. Like our growing caffeine intake chasing a vanishing high, our appetite for fear demands ever more extreme stimuli to trigger the same neural fireworks.

The actual inner workings of what happens when we watch scary movies is quite a bit more involved and I don’t feel qualified enough to describe it in detail. However, the basic principles are such that the amygdala (which is our brain’s fear centre) is activated when we watch them, fight-or-flight response loops reliant on adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol are engaged and somewhere downstream of all of those we end up triggering the dopaminergic reward system for having survived the fake ordeal.

And as we watch more horror movies, the amygdala “learns” that what we watch is not real, the adrenal system becomes desensitized and, because as a result of frequently engaging the dopamine system we end up forcing the brain to build more receptors to respond to increased levels of dopamine, the reward effect becomes less pronounced. As we watch more horror movies, they become less scary, and we end up seeking out more intense thrills in pursuit of triggering these complex cascades and giving our brain the reward that it craves.

How this translates to reality is that while an avid fan of horror might embark on their genre journey watching classics like Halloween or Poltergeist, it’s only a matter of time before they descend down the rabbit hole of extreme subgenres and end up binging Martyrs while munching on nachos as though it was a harmless rom-com in the vein of When Harry Met Sally. This is a known phenomenon described across many cultural interfaces, and in some respects it is seen as problematic. Specifically, similar processes govern the widespread addiction to online pornography among young men and boys who—thanks to unfettered access to all sorts of explicit imagery at the push of a button courtesy of powerful pocket-sized computers glued to the palm of their hand—end up seeking sexual gratification from watching increasingly extreme content that invariably alters their perception of reality or understanding of real sexual interactions they might expect to have with another person.

However, while deprogramming millions of males and unmooring them from their flagrant addiction to seeking sexual satisfaction from watching progressively more intense content that frequently veers into criminal-adjacent depraved fantasies, the matter might be much simpler when it comes to our generally understood relationship with the horror medium, at least in the cultural mainstream. And that’s because what I think governs it is a self-correcting feedback loop.

Imagine what it would be like if your brain realized that building new adenosine receptors in your brain was self-defeating because you would respond to this process by simply ingesting more caffeine, most likely at your own peril. After all, coffee is also a potent diuretic and in pursuit of that buzz of energy you’d deplete your electrolytes so profoundly that you’d most likely end up seeing adverse health effects, like cramps, shivers and worse. But what if your brain decided to build different types of adenosine receptors that caffeine would no longer “fit” to break the feedback loop and politely send you to bed the minute you’re tired? Coffee would no longer work, and you’d have to look for other stimulants instead. Or maybe you’d just learn to take regular breaks and get enough good quality sleep.

Because what we find scary is quite a bit more complex—as I remarked above: amygdala, adrenal activation, endorphins, dopamine reward and all that jazz are involved—we do have ways to introduce such circuit breakers, though we don’t seem to be doing so because of the way movies become more extreme. It happens thanks to financial diminishing returns, random black swan events and completely unpredictable box office traction of weird indie movies coming out of the left field.

When the slasher era of the 80s and 90s was in its death throes, even despite its brief revival owing to the success of the Wes Craven-directed Scream and its band of imitators, along came The Blair Witch Project and found footage horror and reset the template. It excised violence from horror movies completely. As filmmakers were running out of ideas for interesting kills or narrative reasons for seemingly immortal icons of horror to come back and hack and slash some more, it turned out that audiences were ready to be scared out of their wits in different ways; ways their amygdala did not know how to classify as fake and thus worthy of engaging that fight-or-flight response cascade and rewarding the effort with a nice helping of dopamine for their troubles.

Interestingly, extreme violence took a life of its own and morphed into torture porn with the arrival of the Saw and Hostel movies, which then refreshed the slasher genre with the remake of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, House of Wax, Wrong Turn, The House of 1000 Corpses and many others. Meanwhile, the mainstream ran on the combined strength of found footage movies and J-horror transplanted thanks to the stunning success of Hideo Nakata’s The Ring, neither of which were reliant on violence nor extremely graphic content in any appreciable measures. Those movies were simply scary and jumpy.

The torture porn craze ended up short-lived because the bigger-harder-more approach quickly pushed the Saw sequels and others (Fede Alvarez’s Evil Dead remake was particularly notorious for its extreme violence) way past the limits of widely acceptable taste that mainstream audiences were prepared to tolerate. The arrival of pre-elevated horror transition period of supernatural horror revival (courtesy of the creators of Saw, James Wan and Leigh Whannell) also came with an admission that violence was not required to scare audiences. In fact, The Conjuring, when originally released in 2013, was rated R only on the back of its intense atmosphere and potent scares. The same could be said about the early elevated horrors of 2014 and 2015 like The Babadook, Get Out or It Follows, which relied solely on generation of suspense, atmospheric buildup of dread, creative scare tactics and thematic novelty of openly inviting the viewer to interpret the movies as socially-relevant conversations.

But as we added more movies to the microtrend of elevated horror, the diminishing returns stemming from that neurochemical adaptation began registering. Some elevated horror movies got more creative (Us), some more convoluted (The Night House). Others, like Ari Aster’s Hereditary, got scarier. However, in a similar manner to late-period slashers that banked on outlandish high concepts and ridiculously heightened violence, graphic imagery became one of the go-to tools for filmmakers to spice up their otherwise intellectual and elevated genre pieces.

Aster’s own movie (as well as Midsommar and Beau Is Afraid) began indulging in strategically positioned flashes of gruesome violence in an effort to keep the audience in a chokehold. Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man and Wolf Man leaned heavily into violence and body horror as auxiliary tactics supplementing their thematic conversations about gaslighting, generational trauma and failures in communication. The same can be said about movies like Antlers, Talk to Me, Evil Dead Rise and others. Violence once more became a mainstay in the mainstream of horror films as it offered reliable ways of upping the ante, keeping the increasingly desensitized audience entertained.

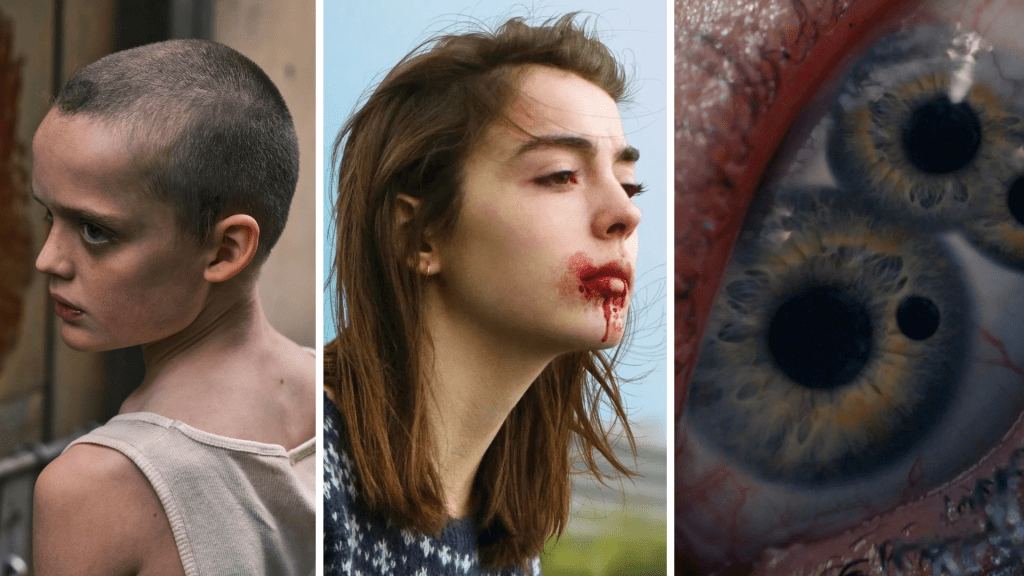

And now we have to reckon with a stark reality that the mainstream horror has been effectively hijacked by body horror, which—and it shouldn’t really be a surprise to many—isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. What started as “elevated horror” has now morphed into “elevated body horror” as movies like Raw, Titane, The Substance, Possessor and Infinity Pool have reignited the kind of post-Cronenbergian sensibility in the genre that might simply be too much to stomach for large sections of the viewership. While it is more than acceptable as a niche with specific appeal, it is now expected that mainstream genre movies like Bring Her Back and Dangerous Animals would feature sequences that will be difficult to sit through. Thus, a clear cultural analogy to the feedback loop between dopaminergic gratification stemming from the pursuit of increasingly extreme stimuli begins to emerge—mainstream horror is being pornified.

When you go to the cinema to watch a movie like The Terrifier, you know what to expect and the whole point of the movie is to be violent and gruesome. However, when extreme content sneaks into movies that are already skillful enough at generating dread, suspense and fear, the added oomph of extreme violence might completely sour the experience and leave the viewer in a state where they do not remember much about the movie apart from the cantaloupe scene in Bring Her Back or the thumb sequence in Dangerous Animals. In 2017, neither of these movies would have “needed” the extra adrenaline because viewers would have been perfectly at home with a suspenseful supernatural elevated horror about grief or a gritty Jaws-meets-Wolf–Creek thingamabob. In 2025, it seems required.

This means to me that we find ourselves at a precipice of change. I don’t know whether the revival of 90’s meta-slasher, where violence seems much more fun even in more extreme guises, like In a Violent Nature, will reclaim the mainstream; though, movies like Ready or Not, Abigail, The Menu or Heart Eyes and Thanksgiving flanked by the continued renaissance of nostalgia-driven legacy sequels to movies like Scream or I Know What You Did Last Summer might be able to create a mainstream alternative to the splintered elevated body horror microtrend. Perhaps what needs to happen is something we don’t know yet. An unknown unknown. Maybe techno-slasher satires like M3GAN and its sequel together with Companion and others can form a movement that keeps violent imagery within the parameters of tasteful entertainment: shocking, spasmodic and just gratuitous enough to keep the intensity levels from veering into the realm of vomit-inducing sensory torture.

Or maybe a wholesale reset is in order, in the vein of the 1999 arrival of found footage and how torture porn itself fizzled into obscurity having gone so deep down the spiral of Rube Goldberg gross-out that only vanishingly small sub-demographics of gorehounds were willing and able to champion it. Horror needs to evolve new ways to engage our fear response because the current state of the mainstream indicates that not only do we see movies fold upon themselves narratively, but the ceiling on the ante being upped is now dangerously close and we are almost out of headroom.

Leave a reply to TOGETHER and the Do’s and Don’ts of Spicing Up Your Elevated Body Horror – Flasz On Film Cancel reply