Anyone born sufficiently long ago will be able to recognize the image of Wile. E. Coyote meticulously planning and staging a complex contraption whereby the unsuspecting Road Runner would waltz into it and end up with an anvil falling on his head only to have that anvil flatten the coyote instead. Every episode without fail we’d watch that poor old coyote make the same stupid mistakes and derive incredible levels of entertainment from it. We’d probably think—seven-year-old little geniuses that we most assuredly were—that we’d never fall for any of that nonsense, now would we? Because we are smarter than that dumb old coyote and why is he even so bent on capturing that Road Runner anyway?

You’d think regular flesh-and-blood people would be able to recognize a trap when they saw one, but sure enough they don’t. From British high-profile politicians allowing themselves to be caught on tape as they offer lobbying services to fake companies all the way down to middle-aged men clicking on links promising to take them places where they can meet women from their area before having their digital wallets ransacked, the world is littered with examples of people realizing they just stepped on a landmine only after hearing an ominous-sounding click and realizing their legs are about to go bye-bye.

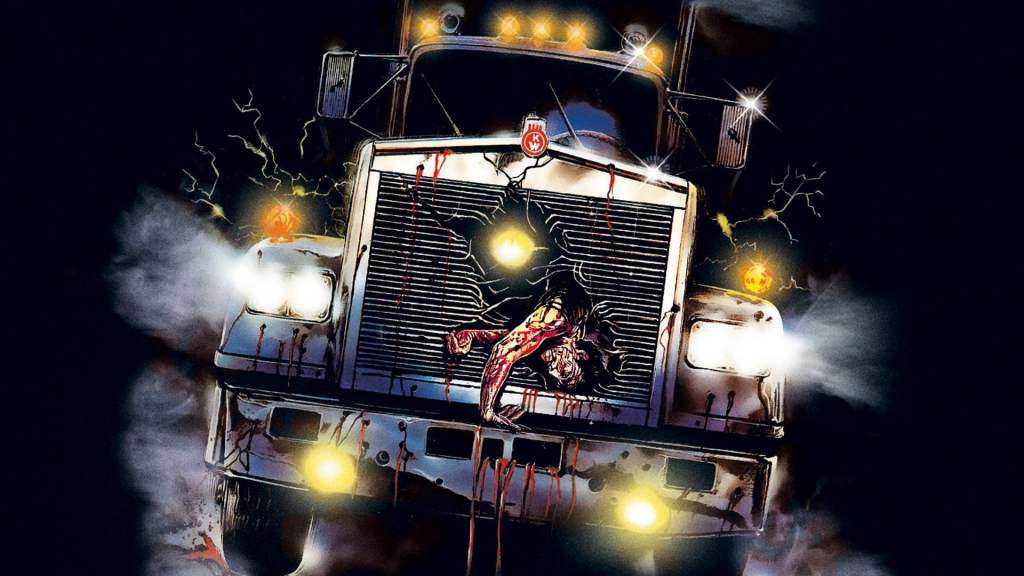

And I believe Stephen King’s Trucks, a short story he penned in 1973 (before Carrie saw the light of day) and had it published in his first collected volume of short stories Night Shift, is one such landmine… which the author proceeded to step on having buried it in the ground himself. And the process of him stepping on that landmine and having his lower half turned to mince was captured on film as Maximum Overdrive.

Now, I’m not here to litigate the craziness which clearly must have taken place behind the scenes as this movie was being made nor do I want to flog that dead horse of critical panning this movie received at the time. There are better sources for you to check out if you are so inclined (Wikipedia is a good start and there’s also an oral history of King’s many adaptations titled Hollywood’s Stephen King which you can pick up and read). Therefore, I will not be litigating whether King was coked out of his mind or boozed off his tits the whole time this movie was being put together with him in the director’s chair. For all I care, the jury is still out on whether King even remembers directing this movie and the state he was in as he was doing so, and it all depends on who you ask. However, at this point I am inclined to believe any and all accounts simply because by mid-80s, Stephen King was riding the wave of his success like a goddamn rock star. Literally everything he had ever written and published was either already adapted into film or television (Carrie, Salem’s Lot, The Shining, Cujo, Firestarter, Dead Zone, etc.) or optioned with a view to being developed into a movie or a TV show in a not-too-distant future. As his surname suggests, King was the king then and therefore he was a guy you probably couldn’t realistically say no to.

Therefore, when I read he decided to ride a hog from Maine to North Carolina where Dino De Laurentiis was staging the production of Maximum Overdrive or when I hear he wanted Bruce Springsteen to play the lead role which De Laurentiis gave to Emilio Estevez (apparently because he had no idea who Bruce Springsteen was, the philistine that he was), I kinda-sorta want to believe them because these nuggets of information seem congruent with rock star behaviour. And what these tidbits tell me as well is that, for the most part, King could do as he pleased. In fact, he had a multi-picture deal with De Laurentiis who had produced adaptations of Dead Zone and Firestarter, both of which ended up making money, and who would continue producing King’s adaptations into the early 90s.

Hence, here I am asking why in the world King would choose to adapt Trucks himself in the first place. Did he feel incredible kinship with the material? Could be. After all, the man has a bit of a rocker side to him and I could see he has a romanticized outlook on the trucker hat-wearing, tobacco-chewing americana, so it makes sense to assume he would want to direct a movie where he gets to film massive articulated trucks whizzing about, destroying stuff and exploding. And if anything, having all of it set to AC/DC (King’s favourite band) would be another interesting selling point. In fact, he got AC/DC to record a soundtrack to his movie, such was King’s cultural reach, which was then released as an album titled Who Made Who in 1986.

Or maybe was the question of adapting Trucks a question of availability of material to adapt? After all, King’s writing was a hot commodity in Hollywood and I wouldn’t have been surprised if most of his work had been ring-fenced already or in various stages of development with other filmmakers and production outfits attached. He probably wouldn’t be able to adapt any of his own novels because those were usually snatched by Hollywood studios long before publication and with typos still in the text, so maybe the pool of material King could work with was limited in this manner. So, for whatever reason—and if anyone out there has solid information on the matter, leave a comment or let me know because it honestly fascinates me why King would choose to adapt this particular short story as opposed to Sometimes They Come Back or I Know What You Need—he landed with Trucks.

Having read this short story, all I can say is—in the voice of Admiral Ackbar from Star Wars—it’s a trap. Any filmmaker wishing to adapt it into a full-length feature film would have to first understand what this story is, what it lacks and how to shape it into a format where it would both make sense and conjure enough entertainment to convince the viewer to stay put until the credits roll. In essence, King’s story transports the reader in media res into a scene where a truck stop in the middle of nowhere has been taken hostage by a bunch of semi trucks driving themselves, which do not allow the people trapped inside the truck stop diner to leave. We don’t know why we are where we are, we don’t know why those trucks came alive on their own, we don’t know what their motives are or if this is an isolated instance or a nation- or worldwide takeover of some description. All we do know is that cars are not affected and—as the final sentences suggest—maybe planes and helicopters may be sentient too, in addition to a suggestion that trucks may be on their way to take over the world, braindead as it may seem to an outside observer unfamiliar with King’s imagination.

After all, I can only surmise that King’s story originated as a glorified what-if scenario, like many of his work. However, instead of “what if Dracula came to live in my hometown” or “what if that quiet kid in the back of the class could lift objects with her mind,” Trucks boils down to a simple “what if those massive rigs could drive themselves and kill everyone who leaves this place.” I imagine King must have thought it up while sipping coffee at a truck stop midway through a massive road trip. He probably thought about it for a second, got back home and typed up the seven and a half thousand words required to complete the story, which by my estimation must have taken him just shy of four days if his self-professed work ethic of banging out two thousand words a day is anything to go by. By no means do I believe that Trucks was a transformative piece of fiction for its author. It reads like a trifle. An experiment in fiction writing and not much more, with a bit of a tongue-in-cheek attitude too. After all, why would trucks know Morse code?

Consequently, because Trucks is just a vignette underpinned by a grand total of not a whole lot, whoever chooses to adapt it for the big screen is required to do some heavy lifting, which begins with understanding the modality of how to adapt it in the first place. Because it’s essentially a one-act scenario composed of three major scenes, there isn’t much scope to stretch out the narrative and introduce reinforcing filler material to keep the narrative from snapping. Adapting verbatim will never amount to a feature-length movie and the only real option is to imagine a bigger story the narrative of Trucks is a part of. Which is where the trap is laid.

What King chose to do to extend the story into a feature-length format was to invest in its world-building and look beyond that truck stop, which at least in theory looks like a good idea. Therefore, Maximum Overdrive starts with an acknowledgment that Earth has found itself in the tail of a rogue comet, a silly-yet-familiar set-up aimed to position the film as a play in the realm of The Twilight Zone. In consequence of this supernatural occurrence, not only trucks come to life, but many inanimate objects do so as well. Electric carving knives, drawbridges, lawnmowers. Even toy trucks. Digital billboards display rogue messages and an ATM calls a random guy (Stephen King himself in a cameo role) an asshole.

However, King didn’t do much more with the world he’d just sketched out. One could argue he had an opportunity to stage a Roland Emmerich-esque disaster piece and carve out a protoplast to Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse (a novel whose adaptation has been bouncing against the walls of the development hell for more than a decade with Steven Spielberg attached to direct and most recently with Michael Bay taking interest). However, to do that, the movie would have to open up the world a bit more and introduce characters pursuing their own stories—even if they’d eventually converge at that truck stop—for a while longer, so as to allow the viewer to immerse themselves in this newly described universe where technology rose up against humans. But King chose not to do that. Instead, he introduced those characters, sure, in a rather cursory way and led them straight to the truck stop.

I think what I’d have found much more interesting would have been if the movie had leaned into the dynamics between those people shmooshed together against their will in the confines of a rather small location a truck stop diner surely is. In fact, this is something King did in The Mist to a much greater extent and with a stunning effect on the narrative and on reader immersion. I believe there was an opportunity there to localize the story and lean into the characters while taking them a bit more seriously, as if to counterbalance the outlandish concept of trucks coming to life, using Morse code and keeping people locked inside four walls. Instead, the movie presses firmly on that camp acceleration pedal and produces an onslaught of tongue-in-cheek craziness, which admittedly is not for everyone.

Who am I kidding? It’s barely watchable because between Yeardley Smith’s high-pitched squealing (an early role before she bagged her iconic place in the cast of The Simpsons), fat people making audible plop sounds while pooping in theatrically filthy truck stop toilet cubicles and a massive truck with a goblin gab attached to its front grille ostensibly leading a fleet of bloodthirsty vehicles, nothing can be taken seriously in the film. And I can only admit that a camp tone works much better when both the filmmaker and the characters in the film treat their outlandish and preposterous predicaments with stone cold seriousness. If they wink at me, camp becomes parody and that’s a whole different ball game.

In effect, Maximum Overdrive fails on all accounts because it uses whatever world-building it has as filler as opposed to colouring in the characters left intentionally flat by King the author and it also fails to recognize how to leverage its own camp proclivities. I get that it’s cool to get AC/DC to produce music for you just as it must be fun to preside over scenes of carnage and destruction, but it just turns out that even the author of the story himself wasn’t able to navigate the process of expanding a short vignette (which was ripe for having something done to it, by the way) and make it a success.

In fact, the 1997 re-adaptation of Trucks for the USA Network came much closer to understanding the assignment laid out by the author. Granted, the 1997 movie was made on a fraction of the budget King had at his disposal in 1985 when he was making Maximum Overdrive (Dino De Laurentiis gave him nine million dollars to burn), so any world-building had to be skilfully downscaled. Instead, the filmmakers (Chris Tomson at the helm with Brian Taggert writing the script) leaned into the character work in the way I wished King had leaned into his own adaptation of this story. They produced a much more intriguing concoction of characters who the viewer actively wants to root for, as opposed to a collection of caricatures meant to function as parodies of themselves. Sadly, this drama alone wouldn’t function anywhere near as well as it should in a movie which is also supposed to sport deadly trucks, so Trucks made for TV ended up a bit too boring for its own good and played out like a car crash slowed down to a trickle.

However, I think there’s a great film somewhere at the interface between Maximum Overdrive and Trucks because the latter of these two adaptations could have surely benefitted from the other’s scale and budgetary allotment, while the former could have taken a page from the way the other one breathed life and three-dimensionality into its characters. But you really need both of these to make any adaptation of Trucks work, which neither King himself nor Tomson and Taggert identified. And if anyone, I would have expected Stephen King to have figured it out. After all, it was his story and at the time of making Maximum Overdrive he had written The Mist, which demonstrated exactly the kind of cabin fever atmosphere his movie could have drawn from.

Instead, what King showed in his one-and-only directorial effort (not a real surprise the car keys were taken away from him between the film’s two Razzie nominations and the unwieldy craziness of keeping King in check on set) was that even the author and a professional storyteller at the peak of his game (perhaps partially excused by the fact he may have been perpetually intoxicated at the time, as the legends go) became a real-life Wile E. Coyote who painted an ACME-branded instant tunnel on a brick wall hoping for Road Runner to bash his brains against. And as you’d expect, the Road Runner ran straight into the tunnel as if it was real, meanwhile Wile. E. King, trying to follow after him, knocked himself unconscious. And then a train came out of that fake instant tunnel and drove right over his poor mangled corpse.

Leave a comment