“John, can I talk to you for a minute?” Rane points with his eyes at a room to the side.

“Oh, yeah.” Vohden is visibly tired and embarrassed of how his family behaves, yapping and yapping about Japanese technology invading their country. He probably wonders if they can even comprehend what it feels like to be an alien in your own country, a visitor through time drop-shipped after seven years in captivity and torture. They probably don’t, too consumed with their frenzied armchair politicking and smoking their see-gars. Both men leave the room.

“I’m sorry about all this major.” Vohden turns to Rane, as though to pre-empt whatever comes next. Rane doesn’t care about it one bit, though. His mind is elsewhere.

“That’s alright, John. I found them,” says Rane.

“Who?”

“The men who killed my son.” Vohden slowly turns his head towards Rane as if to fully process what he just heard. He only needs a few seconds to understand what needs to be done.

“I’ll just get my gear.”

What a line. I’ll just. Get. My gear. Five words is all that’s needed to encapsulate an entire conversation’s worth of dialogue. In fact, this whole exchange—eight sentences in all—packs such an immense punch that it is almost unbelievable. At this point I cannot be sure if the genius of this writing can be attributed to Paul Schrader, who wrote the original draft of the Rolling Thunder screenplay, or to Heywood Gould, who came in later to rewrite the script. If Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation is to be trusted, it is Gould who is likely to be responsible for writing this lean exchange imbued with incredible depth of flavour. After all, apparently only a handful of lines originally penned by Schrader were left unchanged, which also infuriates Schrader to this day.

But why is this conversation relevant? Why are those words important at all?

The simple answer is because it’s probably one of the coolest exchanges in the history of 70s Hollywood, and one about which very little is known. Everybody is aware of the Indianapolis speech in Jaws or about Rocky Balboa’s “What about my prime, Mick,” or even the infamous “You talkin’ to me” mirror monologue in Taxi Driver. All these examples—and there are many more I have missed, I’m sure—became iconic for a good reason, as they speak to the power of their characters, inject emotional rawness into them and relate to themes underpinning the movie.

This is also the case in Rolling Thunder, a movie most filmgoers these days are completely unaware of or maybe they don’t pay attention to it in the way they would to a Scorsese or Spielberg movie from the era. In fact, with a small exception of a few voices, Tarantino being one of them, this movie has been consistently overlooked and summarily dismissed as a violent revenge flick, a fascist wish fulfilment fantasy and as such not a lot of attention has been paid to what Rolling Thunder actually deals with. But it deals with a lot.

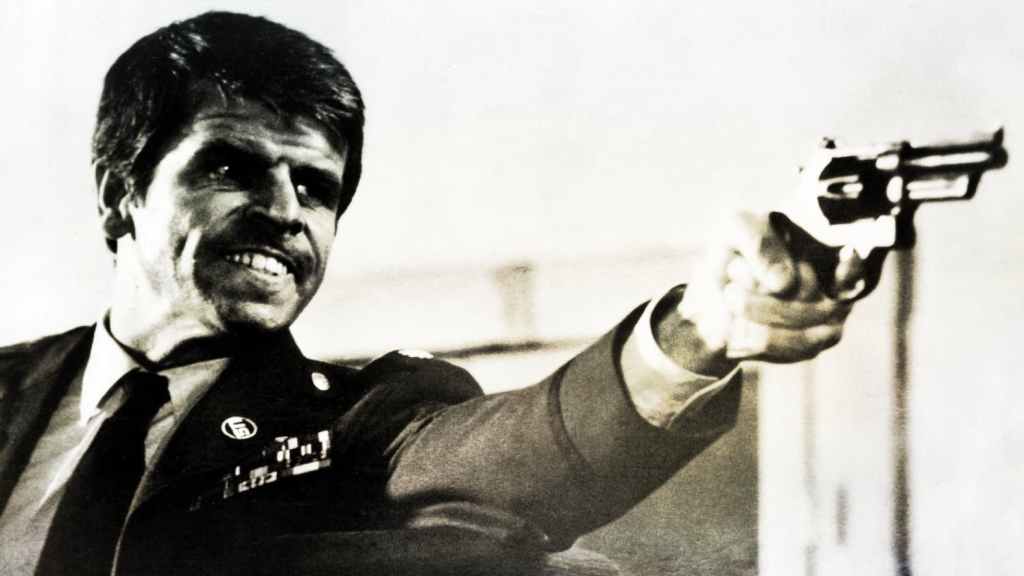

This 1977 movie assumes the guise of a prototypical revenge movie that capitalizes somewhat on, or maybe reflects upon, the post-Vietnam War malaise gripping America of the time. In it we find Charles Rane (William Devane) and Johnny Vohden (Tommy Lee Jones), two former POWs who are returned to the country with great fanfare. Rane becomes a local celebrity despite the fact he has absolutely no idea how to reintegrate into society, nor does he have the tools to achieve it. He hides behinds his aviator sunglasses and puts on a show, pretending to the outside world that he is not completely numb and withered on the inside.

Rane’s wife has since moved on. She accepted a marriage proposal from someone. Rane’s son doesn’t recognize his dad. Why would he? Rane left for Vietnam when he was merely a toddler. Meanwhile, the San Antonio officials parade Rane like a war hero, a celebrity. He’s given a brand-new Cadillac and a chest of silver dollars, one dollar for each day of captivity. Two thousand five hundred and fifty-five in all. Plus one for good luck. But neither the money, the car, nor the fame can help him assimilate into normal life. He sleeps in the sewing room, away from his wife and son.

Things change on the day his house is invaded by a gang of criminals demanding he hands over the silver dollars he received. They proceed to torture Rane… not knowing he’s a professional at dealing with pain. Eventually, they grind off his right hand in a sink garbage disposal, only minutes before his family walk in and are taken hostage. Criminals get their dollars. Rane’s family is executed. Rane himself is shot in the chest, but he survives.

Which is when his hitherto dormant sense of self awakens, thirsty for vengeance.

That’s mostly it. Rane goes on a quest to find those responsible for murdering his family, picks up a sidekick (Linda Haynes) along the way and everything ends with a roaring crescendo of carnage somewhere in Mexico, thus forever sealing the fate of this movie as an apotheosis of violence and a tacit acknowledgment of anti-immigrant sentiments some viewers accused Hollywood filmmakers—specifically genre filmmakers—of holding.

I believe it is not only incredibly myopic but also terminally disrespectful to the thematic scope embedded in the movie, placed right under the epidermis of its primary narrative referring to and capitalizing on the legacy of a fundamental revenge western archetype like The Searchers. At the very core, Rolling Thunder is a treaty on male mental health that comments on ideas which continue to be neglected to this day. I suppose similar comments could be levelled at Taxi Driver, Hardcore, Death Wish and other canonical genre works of the decade, albeit each with their own bespoke flavour to them, but the point remains that Rolling Thunder is the easiest to unpack without immediately running into a problematic territory of attempting to rationalize the headspace of a deranged sociopath on a killing cycle (Taxi Driver), a domineering father crippled by his own repressed sexuality (Hardcore) or an unhinged former liberal with a self-conferred permission to lash out and lean into his own dormant fascist tendencies (Death Wish).

Charles Rane is mostly devoid of such problems. In honesty, he is a husk. An empty shell of a man who arrives back on the American shore completely ruined internally and whose plight is met with a pat on the back, a handshake and a gold watch for keeping his upper lip stiff through all those years. This is a familiar image because all throughout history men have been seen as mostly disposable. Nobody ever batted an eye at the idea of shipping entire legions of young men into war and then welcoming those fortunate to make it back in one piece with nothing more than a shallow expression of gratitude and literally no framework for them to reintegrate into society.

Consequently, Rane is left to his own devices. He’s a de facto time traveller who doesn’t understand the culture he is in, doesn’t have any meaningful point of reference to develop a relationship with his son and he is expected to just get on with life. Which he can’t because he is quite clearly dead inside. He’s numb and cold. And what is more, he is asked to talk about his feelings, both by his wife (Lisa Blake Richards) and by the army therapist (Dabney Coleman).

Problem is, like many men, Rane simply doesn’t have the toolkit to express his emotional state using verbal means and in contrast to many women—for whom talking therapies tend to work very well—the single idea of talking through his issues isn’t enough for Rane to fix them. He’s a creature of action, not words. In fact, Rane’s character is written in such a way that you’d be excused to think that William Devane was paid by the word and he wasn’t interested in earning much money. He’s a monosyllabic, stoic persona who internalizes absolutely everything and expels only the absolute minimum calories by speaking.

That’s because he ostensibly doesn’t need to speak to anyone, and also he came to learn during his years of captivity that silence was a tool needed to triumph over his captors. He’s a doer, not a talker. Like John Rambo. Or Dirty Harry.

What we find as the film unfolds in the aftermath of the home invasion which resulted in Rane’s family gunned down and him becoming a one-armed cripple, is that Rane needs a mission to begin healing. Therefore, he immediately embarks on a quest to find the culprits and despatch them to kingdom come. He learns how to load shells using the hook which replaced his mangled hand. He preps his weapons, which includs sawing off the barrel of a rifle he received as a welcome home gift from his young son. He goes on a scouting expedition to figure out who these people were and where they live. This is the first time in the film we see Charles Rane actively propelling himself through life as opposed to reacting to external stimuli.

Question is: would his family still be around had he been taken care of by someone who knew that Rane needed a purpose and a mission in life instead of an invitation to talk about his trauma? Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe the Acuna Boys would have still invaded his house, taken his money and killed his family. Or maybe Rane would have developed the necessary tools to deal with his trauma and would have moved out long before, right after learning his wife had moved on years earlier. That way, the home invaders wouldn’t have had the opportunity to come across his young son, because he’d live in a different house.

Unfortunately, Rane never received any substantive support and was implicitly asked to just suck it up and get on with life, which we all know he was not equipped to do. What he needed was a mission and this sentiment is reflected once more in the conversation cited at the top of this text. When Rane informs his friend Johnny Vohden, who by the way had briefly come back to support Rane after his family was murdered, that he found men who killed his son, Vohden just knows what needs to be done. Rane isn’t there to talk it through or to cry into Vohden’s shoulder. Both men—equally numb on the inside—appreciate the futility of talking about their trauma. They know it won’t help.

But you can see the expression on Vohden’s face change the minute he realizes what Rane is telling him. He is inviting him to join on that quest for retribution, to stand shoulder-to-shoulder against an enemy and incur their collective vengeful wrath upon them. And Vohden almost perks up. He comes alive. He is no longer a walking and talking zombie but a man on a mission. For Vohden and Rane alike, the process of healing and finding direction in the world they barely recognize begins once they understand their renewed purpose to exact vengeance.

“I’ll just get my gear,” says Vohden. Nothing more is needed. They both know what needs to be done. The purpose is set. Granted, their purpose involves a violent multiple murder and reckless endangerment of many bystanders, which is a criminally bad idea outside of the parameters of a genre movie, but the point still stands that Rolling Thunder illustrates just how poorly equipped we are as a society to address male trauma and mental health issues. In fact, we are almost purposefully ill-equipped in this regard because the tendency is to dismiss those issues, hide them under the carpet and look the other way pretending they are no concern of ours.

It is way easier to stick labels on troubled men than to actively think of developing tools specifically for the purpose of helping them. Even contemporary cinema reflects these sentiments (Leave No Trace) and suggests that men like Charles Rane would be left behind even in times where awareness of mental health and PTSD is at an all-time high. Yet, the cultural expectation persists that men ought to open up and talk more about their troubles. Meanwhile, it might be easier to give them a purpose and let them get their gear.

Leave a comment