A few days ago at this point, and in this era of supercharged bullet-sized consumption it could as well have been last year, Twitter (sorry again, X) became abuzz with opinions, quote tweets (or reposts, I suppose), snappy comebacks and even more profoundly insidious methods of engagement when someone posted a snippet of a review of what I think was the upcoming Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga that opened with a paragraph’s worth of a personal anecdote and opined this sort of thing had no place in a film review.

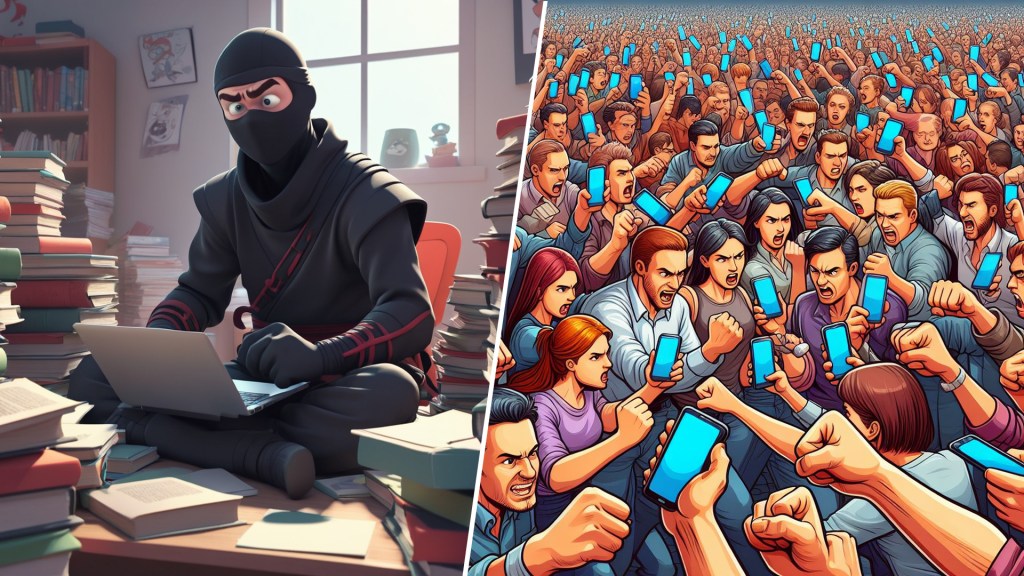

The tweet generated enough engagement to briefly become the talk of the town and, as bad luck would have it, attracted considerable and unfiltered vitriol from some corners of the Film Twitter community which tend to be particularly fond of sniping from behind the blast shield of anonymity provided by their online avatars. Therefore, this post no longer exists and its owner has deactivated their account. The simple fact a person has been effectively hounded out of the marketplace of opinion on the back of having one, however controversial it may have been, would be enough to draw attention and generate a conversation about the spectrum of hostility permeating the online movie community as a whole. In fact, I might come back to this in some guise once I have meditated on it for a bit longer.

For the moment, I’d like to download my thoughts on this seemingly controversial topic of whether a personal anecdote has any place in a film review, if writing in first person is a big no-no and who a film review is for these days anyway.

Not that anyone cares, but I may have already voiced my opinion on the role of a review in the current landscape of entertainment where audiences are voting with their wallets and prefer not to come back to cinemas because staying at home and consuming content on their TV screens and mobile devices presents itself as a more attractive alternative to dishing out loads of money for a ticket to see a movie they are unlikely to enjoy unless it comes branded with IP they explicitly recognize.

Before the Internet came and democratized the idea of having opinions on things and having those opinions reach people way outside one’s immediate circle of friends and family, a film review had a job to do. A critic was there to tell you what they liked and what they didn’t. To give you all the facts about the movie playing in your local cinema this weekend and help you make an informed decision as to what you should spend your money on.

But those days are long gone. In the era of review aggregators that also include audience scores, like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic, all I need to make that decision is contained within a score. 83%? Certified fresh? An audience score of 79%? All good, then. Quick scroll through some of the blurbs on the website, maybe a short google search and a brief visit to your social medium of choice and you’re good to go. You’ve got enough facts to make that decision. You don’t have to read eight hundred words on the matter.

Therefore, here I am telling you that a film review is effectively superfluous, and nobody truly requires my insight to make sense of what to go see this weekend at the multiplex, or what to choose out of the veritable myriad of movies and TV shows available on streaming services. And your average Joe and Jane know that. They don’t care about your “objective review” (if such a thing even exists) or your factual analysis of what the movie is about, what it attempts, where it succeeds and where it falters. I’d even go as far as to suggest that “serious film reviews” are almost exclusively consumed by other film critics who probably have already seen the film they read about, so what are they supposed to extract from your writing? I suppose they might learn something from examining your take on things and maybe (most likely, in all fairness, because many critics wear their opinions like tribal tattoos) disagree with you on some level. But they do know all the facts. They have probably connected Immaculate and The First Omen to Roe v Wade themselves. They have probably taken sides in the debate around Alex Garland’s Civil War. So, why should they read what you have to say?

In fact, why should anyone read what you have to say? What makes me special as a writer? Why do I do what I do? Who do I do it for?

Look, let’s not kid ourselves. Nobody cares about your analysis of The Kissing Booth 3 or your praise for that new Marvel movie. As a “critic” in this modern landscape you are for the most part a cog in the machinery of entertainment marketing and the best you can do is shine a spotlight on that little indie movie you loved that actually needs someone to be its champion. Cynically speaking, even this doesn’t matter because nobody will remember what you had to say about it in ten years. My critical deconstruction of Heat as a superhero movie won’t be examined by future historians. Neither will my stream-of-consciousness piece on Speed or my rant about Jaws not being a pandemic movie.

So, why bother?

A “professional” critic will be able to answer simply by referring to the monetary value of writing for a publication. And that’s fair enough. However, in the age of AI, it takes me literally five minutes to feed a GPT-4 engine a set of bullet points about Jaws and concoct a perfectly polished piece giving me all the facts, raising all the points of critical importance, all in the blink of an eye. So not only is the informative aspect of a review completely obsolete because a viewer can refer to their social media, friends or aggregators for bearings, but also online publications can pump out content festooned with ads that looks as though it was written by a paid professional without actually paying one to do it.

In that case, anecdotal experience is all that’s left. Your own proclivities. That one little hook in the movie that made you think Love Lies Bleeding was a Coen Brothers movie. That personal connection that made you see yourself a little bit in Sam Witwicky. AI can’t do that. AI doesn’t think unprompted. Not yet, at least. That’s why I gravitate to writing where I can detect a voice behind it and if it takes a paragraph of recounting that time when they were slinging popcorn at a cinema in Leeds or whatever, so be it. At least it feels real. Connected. Tethered to something that matters to someone. Personal writing has the ability to touch someone in ways that “objective” analysis just cannot.

And fine. Call me unserious. Unprofessional. Great. I don’t see myself as a critic anyway. In fact, I don’t know what I am because I don’t write for money or kudos. To be perfectly honest, that since-deleted tweetpost on TwitterX made me not so much realize, but rather reinforce my conviction that I write predominantly for myself. Which is why I write the way I write. In first person. And I sometimes start sentences with conjunctions. Quentin showed me it’s fine and I’ve since rolled with it.

And I don’t care. I write the way I write because I have a compulsion to do so and if serious critics think they’re superior to me because they stay at arm’s length from their work and it makes them feel good, I’m happy with that. You go and feel superior. Meanwhile, I’ll keep writing about stuff I feel the need to write about in the manner I see fit. And if there’s someone out there who stumbles upon my weirdo piece about Fast and Furious movies and how weirdly titled they are, and likes it, I’d be glad.

But I’ll be glad even if they don’t because I write what I write because I love writing. I can’t imagine a world where I don’t and if you took away my laptop, I’d just write on napkins. Can’t help it. And those napkin scribbles? They’d be written in first person too.

We live in an era where the critic no longer has a job to do and their relevance to the culture at large is shrinking by the day. So, I can only surmise that if an open-access LLM can write content better and quicker than anyone else and fulfill the main mission of a film review, such as it is, then all we can do is tell stories. And watching movies makes me want to tell stories. Some of them are more interesting than others, that’s for sure. Some are more personal than others. Some are more mundane. But if Paddington 2 made you rethink your life, I want to read about it instead of wading through stacks of adjectives about how scintillating the performances were and how dazzling the compositing was.

Writing has always been a form of self-expression, not just a means of producing content. Without a voice, you’re not a writer, but a typist. And I know which one I’d rather be.

Leave a comment