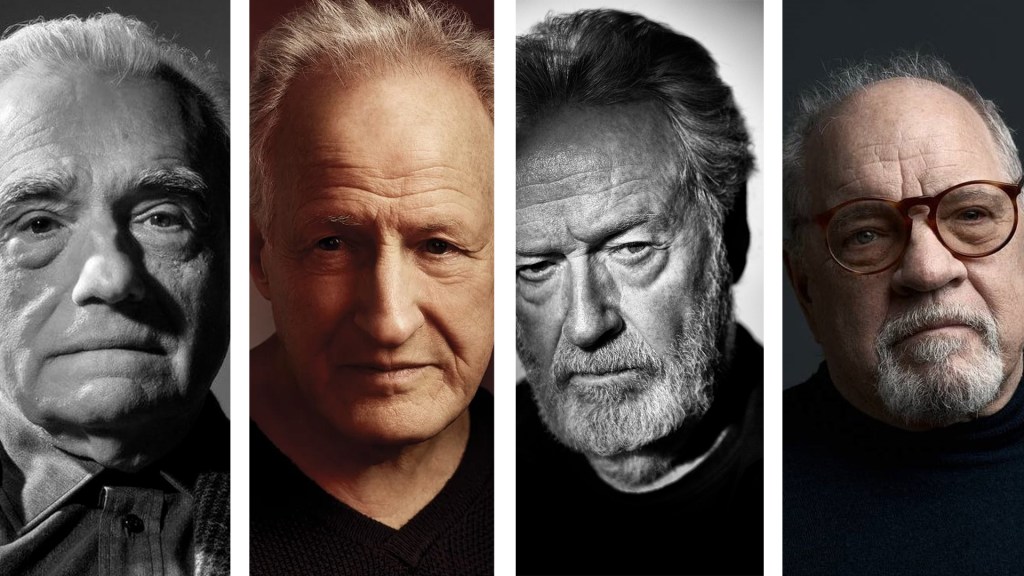

Martin Scorsese is 81 years old. Clint Eastwood is 93. Ridley Scott – 86. Francis Ford Coppola is 84. Paul Schrader is 77, and so is Steven Spielberg. Michael Mann is 80, Woody Allen is 88, Brian De Palma is 83. Isn’t it scary to realize that all those titans of cinema, and many more I failed to acknowledge, will leave this vale of tears within the next ten years or sooner? And they know it.

It is only natural for filmmakers in their Lebensabend to slow down and reflect on their work, look upon their output, consider what their legacy would be and perhaps make a few last-minute adjustments or comments they’d like to leave on. Some, like Scorsese and Schrader, have truly embraced the frightening notion of having maybe the last few precious years before they either shuffle off or their health deteriorates (and it may come suddenly even to the most vivacious octogenarian) so much that they won’t be able to continue their creative work. It’s impossible not to see Scorsese’s The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon as attempts to wrestle with his own legacy, his thoughts about America and maybe even on Hollywood. I think there’s a good reason why Scorsese inserted himself into the coda of his latest movie, thus making it even more powerful, and that reason is partially connected to the fact that he may not get too many more opportunities to articulate thoughts he may have been carrying for a long time.

The same goes for Paul Schrader who has spent the last seven years conceptualizing a grand trilogy dubbed as “The man in a room trilogy.” Arguably his ode to Bresson (and if you follow Schrader on Facebook you’ll know he uses the word “Bresson” more often than Valley girls use the word “like”) the triad of First Reformed, The Card Counter and Master Gardener are meant to be read as reflections on America, but I think you’d be also correct if you saw them as reflections – and maybe even a form of penance – on Schrader’s own artistic output, connected at the hip (much like many other movies he wrote and/or directed, like Hardcore and Rolling Thunder) to his breakout hit Taxi Driver. It is frankly undeniable that Schrader feels the pressure of time much more than he’d perhaps like to admit and that his latest movies are a way of making sure his legacy would be clearly understood.

Michael Mann, another octogenarian in residence, is no different, as he has finally put together his long-gestating passion project about the tumultuous life of Enzo Ferrari. Like Scorsese and Schrader, he too seems to grapple with the footprint of his work and the mark it might have made not only on the world at large but on himself and those closest to him. He seems to be acutely aware that he might not get too many opportunities to make new movies, and even those he is currently engaged in producing are distinctly connected to the works many of us hold in high regard, not only in the context of Mann’s own work, but cinema as a whole.

Francis Ford Coppola is about to come out with his ephemeral piece Megalopolis. Terry Gilliam has finally put together his troubled movie about Don Quixote, never mind all the trials and tribulations, cast changes, catastrophes and calamities. Ridley Scott is back making the kinds of movies that took him to the pinnacle of prestige acclaim. He’s currently out there somewhere shooting a sequel to his Oscar-winning Gladiator and if anything, he seems to be speeding up rather than slowing down. After all, in the last few years he has directed three movies: The Last Duel, House of Gucci and Napoleon. Maybe, if stars align, he will return to the Alien franchise before letting out that last gasp.

Even William Friedkin, before parting ways with this world, managed to reconnect with what I can only describe as a piece of material he must have had a personal connection to. After all, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial doesn’t look like a movie “Hurricane Billy” Friedkin would have ever made, being a stout courtroom drama leaning heavily on theatrical range of its principals, as opposed to the Herzogian rogue spirit that drove Friedkin to bridge the gap between reality and illusion at the time when he was the biggest game in town.

It all feels… eerie. Final. It is as though we were about to experience a seismic shift of some description and all those filmmakers, iconic in their time and (with some exceptions) well-regarded until present day, somehow felt that not only their time on this planet was coming to an end, but that cinema as a form of creative expression was about to change. What frightens me more is that the more I think about it, the more certain I am that this impending transition in what cinema made in Hollywood means will be precipitated not by an external factor or a combination thereof, but by the simple fact these titans of New Hollywood will no longer be here to steward the medium and ensure that at least in spirit it remains in the twilight zone between entertainment and art.

That’s right. Cinema as we know it may be coming to an end because Scorsese, Eastwood, Scott, Mann, Schrader and many more (Milius, Allen, etc.) will soon leave this Earth. Sure, change is inevitable, and their mere presence has never been a guarantee of any status quo. However, simply because we can still expect a new Scorsese movie at least in theory, we are somehow tethered to the 1970s – an era where the blockbuster was born and when some of our favourite movies came out. It was fifty years ago. And it doesn’t even register because many of the icons of that time are still with us. Only after they go will it feel – perhaps completely out of the blue – as though things have changed for good.

When Scorsese, Mann and others leave this mortal coil, we will be left completely undefended from the seemingly ceaseless push towards turning Hollywood cinema back into artless content generating engine it was in the era of sandal epics and cheap westerns, all driven by committees of producers and studio execs… and bankrolled by Wall Street fat cats.

And I wonder who we can count on to pick up the slack and remain as flagbearers of artistic expression. Tarantino is on his way out. Rodriguez is happy doing whatever it is he’s doing. Soderbergh – same thing. Fincher – same deal. If anything, he begins to look as though he suddenly felt the unwavering march of time as well. Will we be left in the world of never-ending Fast and Furious sequels and spinoffs? Can we count on Christopher Nolan to hold the fort? Will Greta Gerwig become the next Spielberg – a spectacle-minded auteur with a knack for meshing entertainment with nuanced drama? Or will we drown in the sea of nostalgia sequels that will eventually fold right back upon itself because eventually kids will grow up having developed second-hand nostalgia for movies they have no business feeling nostalgic about?

I don’t know. I’m not sure either if this is the kind of “fin du cinema” Jean-Luc Godard had in mind. But it is the kind of anxiety that occasionally jolts me into random states of alertness, especially seeing how many of the filmmakers I hold near and dear to my heart are effectively standing over their own freshly dug graves.

I shudder.

Leave a reply to GLADIATOR II and Milking Functionally Redundant Franchise Nipples – Flasz On Film Cancel reply