Ken Loach turned eighty-seven this year and in one recent interview admitted that The Old Oak might very well be his last film. And if it were in fact the case, I don’t think he could have wished for a more fitting epilogue to a life devoted to activism through filmmaking, because this newest production of his feels accordingly familiar, all-encompassing, and eerily final.

Loach opens his movie with a scene where a bus full of Syrian refugees arrives in what could be any of a thousand little towns in the North of England that both the government and God have forgotten, all to the accompaniment of racial slurs and shouting coming from a group of local men visibly agitated at the sight of foreign-looking faces. They taunt them and mock them with glee, seemingly fearless and cocky. We are then introduced to Yara (Ebla Mari), who has her camera taken away from her in a taunting manner and destroyed after a short scuffle. The small crowd of alienated and frightened families slowly disappears into their accommodation in visibly rundown terraced houses, as their hosts can only offer apologies.

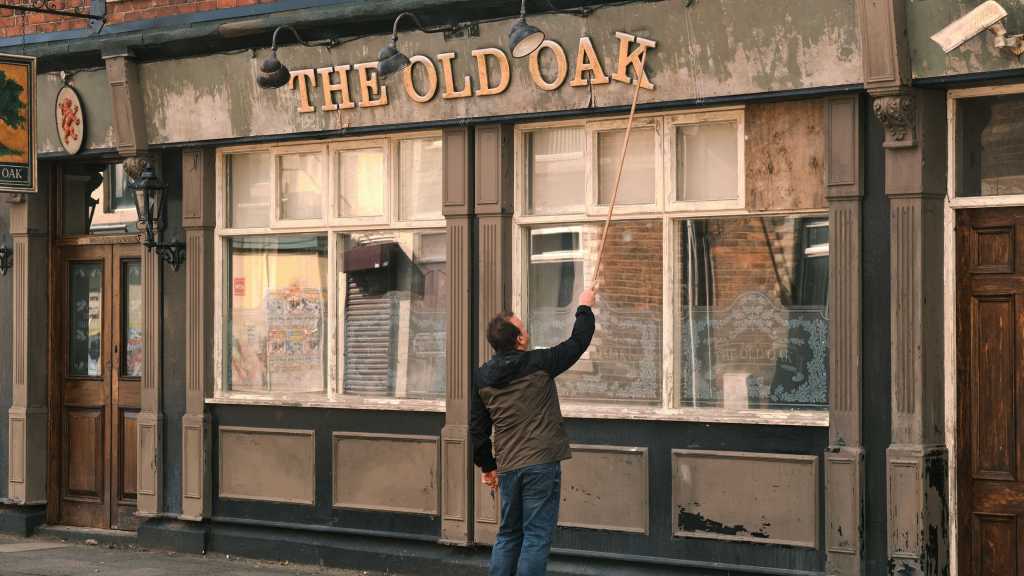

Later, we find Yara again as she visits upon the local pub, the titular Old Oak, run by TJ Ballantyne (Dave Turner), hoping to find the man who broke her camera or to find a way to fix it. While a small group of patrons scoffs audibly, clearly threatened by the thought a young Syrian girl with a broken camera and a lot of pain behind her eyes could somehow herald their eventual displacement from the local population, Yara and TJ spark up a friendship – even though they might not be aware of it at the time – as they find they are somehow connected. They both come from a world which has been erased from the map: one by bombs dropped relentlessly by a brutal regime, and the other taken apart by years of governmental neglect. And as they come to realize it, they also find that what connects them is their fundamental humanity, which then drives them to bring something to their community in an attempt to instil some much-needed hope in its inhabitants, both indigenous and the newly arrived.

Such is the premise of The Old Oak, which could perhaps stand accused of retreading the ground Ken Loach has covered in the past. But then again, you could level such accusations at most of his movies anyway, as Loach has been consistently driven by a singular obsession throughout the many decades he has been active as a filmmaker. From Poor Cow and Kes to I, Daniel Blake and Sorry, We Missed You – separated by nearly six decades – Loach’s output could be likened to that of an ardent campaigner for social change. He’s always been there to champion the cause of the marginalized and forgotten working classes in Britain, downtrodden and put down by the machinery of Tory oppression.

Therefore, it is perhaps a fool’s errand to assume Loach would somehow change tack or soften his worldview, even at the time he is clearly aware of his time on this planet slowly running out. In a way, The Old Oak is just as caustic and just as biting as any of Loach’s most well-known kitchen sink works. However, you wouldn’t be wrong to point out that the movie is filled with thematic conveniences strung together to form a narrative Loach was interested in using to continue his intrepid fight against all forms of inequality. But although it may be correct to note their existence, I don’t believe it is right to hold them against the filmmaker, or the film itself.

And that’s because, as much as it looks like one, The Old Oak is not necessarily best described as a work of cinematic realism in the vein of Tony Richardson, or Vittorio de Sica. In fact, I’d probably go out on a limb and maybe extend this definition to most of his movies because although they use the visual language of such cinema, they almost always venture beyond the plane of the real and enter the universe of a parable, where it is perfectly allowed to string conveniences together because what matters is the message advanced by the narrative, not the veracity of the story itself.

Thus, The Old Oak brings a whole stack of themes and ideas together, from the plight of refugees having to experience racism and persecution in a country which offered them sanctuary, to the fact that in one of the richest economies in the world millions of children go to bed hungry. Loach truly takes an all-encompassing look at the state of Britain and comments on the plague of brainless youths keeping dangerous dogs, out-of-control teenagers succumbing to a life of crime because they feel they have no other alternatives, the bottomless depression of hard-working men and women who have spent entire decades hoping to catch a break that never ever came, the fact that faceless corporate conglomerates are quietly pricing out regular people from their neighbourhoods, all framed by the familiar refrain of the Westminster government never bothering to even notice that Britain exists north of Watford.

And in that quagmire of thematic and narrative conveniences Loach plants a message that seems as timely as ever at a time when another war is brewing in the Middle East – a message of hope and unity. He uses a rather poignant and innately strong statement throughout the film – “those who eat together stick together” – as an indispensable chorus and a thematic glue keeping all these smaller ideas together, like a skilled preacher would. For a change, Loach wants us to emerge uplifted from the darkness of the cinema, yet he’s not one to give you a Hollywood ending either.

The Old Oak is a biblical parable, not a fairy tale. Delivered with assured charisma of a seasoned veteran of cinematic activism, Loach’s likely final movie is a confluence of everything this filmmaker-stroke-campaigner-stroke-activist has been consistently interested in all throughout his life, as well as a call to all those likely to pick up the baton after him to remember what the goal is. He wants us all not to let those greedy Westminster shysters apply the old “divide and rule” methodology. Not to allow those snake oil salesmen to convince us that refugees from war-torn countries are a threat to you.

Loach wants us to always remember that regardless of our heritage, we are all in this together. Through The Old Oak he advances a powerful and beautiful message. He may be using a difficult language and visuals some may find uncomfortable or maybe emotionally manipulative, but rest assured, there is a purpose to all that. He wants this movie to be “The Parable of TJ and Yara”, a story to be recounted by future generations as a vehicle for selflessness and unity in the face of adversity and utter hostility coming from literally all directions.

Therefore, it is best to treat The Old Oak more like a spiritual experience than like a political statement, even though it definitely could be one on its own terms. It is a story from The Gospel of Ken, full of thunderous moral backbiting, heightened overtones and driven by a message fit to become a backbone of a sermon or a blood-curdling political rally. In short, it is everything you’d ever want from a Ken Loach movie, especially one touted as his final word on the matter.

Leave a comment