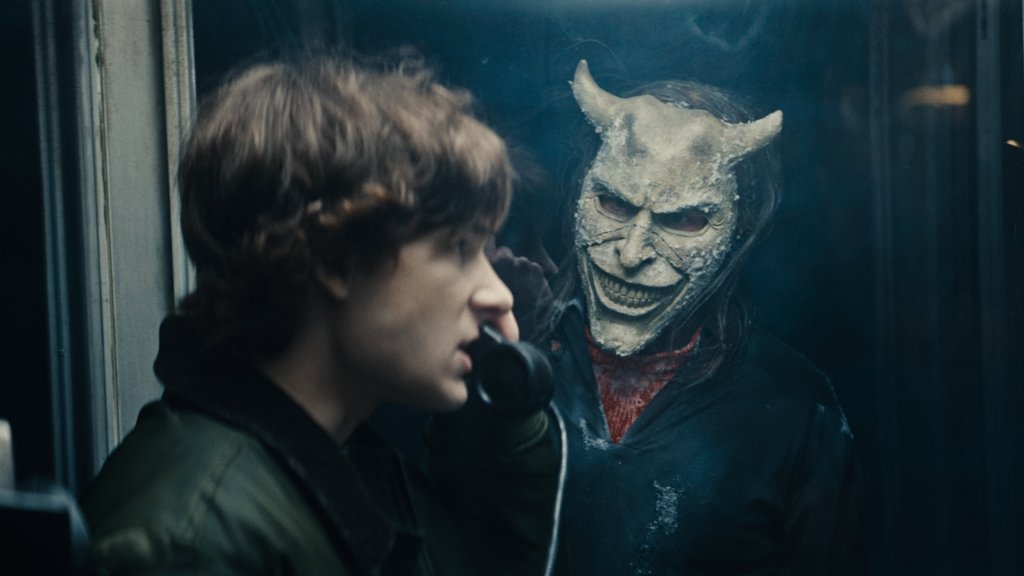

Scratching at the surface of the 2021 The Black Phone is in my humble opinion a required exercise to fully comprehend what its sequel, Black Phone 2, is doing and whether it succeeds or not. The Scott Derrickson-directed adaptation of Joe Hill’s 2004 short story (collected in the volume 20th Century Ghosts later retitled as The Black Phone and Other Stories) turned out to be a success, most likely owing to the combined strength of its young leads (Mason Thames and Madeleine McGraw), the visual prowess of Ethan Hawke’s The Grabber and his iconic set of masks and the period setting that gave the movie its characteristic Stranger Things feel.

Now, I wasn’t the biggest fan of the film as I failed to connect with what I saw as unnecessary potty-mouth screenwriting that felt forced, as well as the visualization of its central gimmick in which Finney, trapped in Grabber’s basement, would engage in edgelordy phone conversations with kids who had died before him. I did, however, appreciate what I saw as a kind of notice-me-daddy energy because the entire premise and visual direction behind the film made suggestive moves towards shaping The Black Phone to function as a piece of Stephen King fan fiction.

After all, it didn’t require much thinking to imagine The Grabber with his Cheshire Cat-grinning masks and jet-black balloons as a nod to Pennywise the clown. In fact, the entire conceit of a movie about a serial abductor snatching kids in a rustic setting was already sufficiently perfumed with It energy. And at this point, having made those connections, it would have been incredibly easy to castigate Joe Hill for trying to ride on his father’s coattails… which would be incorrect because none of those artistic decisions stemmed from his short story. The source material for the book was incredibly sparse in this regard and confined itself to a rather condensed storytelling in which Finney is abducted by The Grabber, who was described as just a bald fat man, and having spoken to one dead boy over the phone ends up killing his captor in much the same way as we saw in the movie. And although those black balloons do feature in the story, it is at the very least far-fetched to connect The Black Phone to It based on Joe Hill’s writing alone. All these ideas came from Scott Derrickson and his team: the masks, the Colorado setting, the spicy dialogue. The works.

This is something I find fundamentally fascinating because despite the fact that the story itself had all the reasons in the world to improvise over Stephen King chords, the movie did it of its own accord. Furthermore, Derrickson claimed to have infused this narrative with his own semiautobiographical musings, as he grew up in Denver in a working-class neighborhood where kids were rarely spared the rod and where afterschool fisticuffs were far from gentlemanly. And yet, if you wanted to make the case that Jeremy Davies’s character of Finney and Gwen’s father was a piece of homage to Jack Torrance, you could perhaps pull it off on supposition alone. In fact, you’d be able to argue that among the many reasons why The Black Phone became such a stunning box office success in the year of its release, this tactile Stephen King connection was likely there too. But Joe Hill had very little to do with it.

What he did though was present Scott Derrickson with what he saw as a killer idea for a sequel, which became the basis for Black Phone 2. Because both the original short story and the 2021 movie ended pretty definitively with Grabber’s violent demise, the follow-up couldn’t simply overlook this reality. It’s not like it was John Carpenter’s Halloween which ended ambiguously with acknowledging that Michael Myers likely escaped following the film’s finale. No, no. The Grabber bit the dust, and it would have been a silly idea to try and bring him back from the dead like an 80s slasher villain. Mental jiujitsu was required.

This killer idea for the sequel assumed that The Grabber would return in Gwen’s dreams, where he’d go on to haunt and taunt her and gradually encroach into her headspace with a clear intention to kill her in revenge for what happened to him at the end of the first movie. In many ways, the central premise was not too dissimilar from Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street. The Grabber would transition from being a flesh-and-blood play on Pennywise to becoming a full-on tribute to Freddy Krueger sans stripey sweater and glove, both of which are subjects to copyright protection, I imagine.

But that’s not even the end of it either. This central kernel of turning The Black Phone into a distant cousin of the Freddy franchise needed narrative and thematic anchoring as well, simply to make sure that the motivation to revisit this world would be rooted in something more than simply wanting to see Ethan Hawke in a cool mask one more time. Thus, Black Phone 2 extends beyond the original into the past and tethers itself to Finney and Gwen’s mother, who had been briefly mentioned in the original film. Capitalizing on the idea that Gwen possessed some kind of clairvoyance (which was also an invention of the movie, as was the character), the sequel manufactures an intriguing connection between her and her mother. In Gwen’s dreams, and with the use of that titular black phone, Gwen connects with her mother who sends her cryptic messages and lures her into visions laced with symbols that may or may not be connected to The Grabber.

In order to deal with Gwen’s progressively more all-encompassing sleepwalking where she is threatened by The Grabber, the siblings decide to find out what happened to their mother. Which leads them to a winter youth camp where she had been a counsellor as a teenager and where, as it turns out, The Grabber murdered his first victims. They end up completely snowed in in the sparsely populated facility, so their only recourse is to investigate their mother’s past, find out who The Grabber really was and face him head on, as he seems to grow in strength and becomes capable of hurting Gwen while invading her dreams.

There’s no debate here: Joe Hill was right when he referred to this conceit as a cool idea as it uses a familiar template of A Nightmare on Elm Street in conjunction with the film’s own iconography and pings back to its own past as well. What I find even more fascinating here—and at this point I don’t have the means to corroborate if this part of the conceit originated with Hill or Derrickson and his frequent collaborator C. Robert Cargill—is that the entire narrative framework once more becomes incredibly reminiscent of Stephen King fan fiction. This time however, It is put back on the shelf and The Shining takes its place instead. Between the secluded location in middle-of-nowhere Colorado, hallucinatory visions slowly chipping away at the characters’ sanity and even the dad coming in to save Gwen and Finney much like Dick Hallorann did in the book, it is once again inescapable and not entirely out of nowhere.

After all, these threads of connective tissue linking the movie to The Shining could be found in the original movie as well. It wouldn’t be entirely incorrect to posit that the dad was already reflecting some aspects of Jack Torrance’s character, especially as he was dispensing “his medicine” to Gwen and Finney with his belt and drowned his unresolved grief in alcohol. In here, though, he’s less Jack Torrance and more Dick Hallorann, though he still rounds out the film’s thematic connection to The Shining because the movie sets its sights on resolving past traumas haunting this entire family, just like the Overlook Hotel amplified the many demons troubling the Torrances.

Therefore, I’d like to say that the idea of smashing A Nightmare on Elm Street and The Shining together while remaining tethered to the iconography and mythos of The Black Phone does look interesting in theory. It’s definitely not an idea anyone ever thought of, but in principle I believe it is worth exploring, especially if the whole idea of setting the movie partly in reality and partly in dreamscapes is visually reduced to practice using aesthetic choices inspired by Derrickson’s work on Sinister. It’s quite fun to see how the movie moves between digital camera work and Super8 as it crafts Gwen’s horrifying visions that eventually begin to threaten her life. It’s honestly pretty cool.

What’s not so cool, though, is that these theoretically intriguing ideas don’t end up going anywhere interesting. Although I can now report that the linguistically spicy writing has become much funnier and more tactile on the second pull, it doesn’t really help the movie to coherently come together and stage a final act that would live up to that wild premise of putting Freddy Krueger in the Overlook Hotel and seeing what comes of it. Eventually, a McGuffin needs to be identified, and a familiar showdown between the clearly demonic Grabber and our protagonists must take place somewhere. And it’s unfortunately nothing but clumsy. Eventually, it’s no longer enough to rely on inspired visuals and cool cinematic ideas. Stuff must happen.

And this is where Black Phone 2 goes from inspiration to perspiration as it devolves logically and becomes progressively more similar to later sequels in the Friday the 13th franchise, as opposed to where it once was, at the unlikely intersection between Wes Craven and Stephen King. Consequently, the movie left me wanting, even despite coming round to paying homage to The Shining with a tableau of the Grabber’s frozen visage. Too little too late.

Black Phone 2 is clearly a movie of two halves and the one where we were supposed to cash in on all those connections and capitalize on the buildup of weirdness, convention took control and all we got was a wet noodle that demoted The Grabber from the position of gradual ascendancy to the pantheon of iconic genre villains to the realm of low-rent usurpers.

Leave a comment